The battle over the inauguration of the electric tramway

This is the thread about the “Battle of South Clerk Street”, or when the students of Edinburgh went briefly to war over the inauguration of the electric tramway system.

I got a book out of the library.

It’s a very interesting book, packed full of interesting tales and knowledge, related by a genuine expert on the subject. For instance, I’m only 1 paragraph in and I just found out that when Edinburgh Corporation (i.e. the Council) took over the tramway system in 1919 it was used as a pretext to relieve all female clippies (“conductresses”) of their employment! Male employees were all kept on.

When the Corporation took over the network, they made the decision to switch from the cable-hauled system to electric traction. Leith already used a modern, overhead wire electric system, but Edinburgh had persisted with the cable system. There were 4 winding houses around the city – at Portobello, Shrubhill, Tollcross and Henderson Row – and these powered endless loops of cables in a conduit underneath the streets. The trams attached to these cables for motive power with a releasable gripper. The system was devoid of overhead poles and wires, but was slow, noisy, inefficient and unreliable. It was also very expensive on account of the endless repairs and maintenance required.

However, the prospect of overhead lines and poles on Princes Street caused something of an outcry in certain quarter. It would, they said, “result in a hedge of scrollwork“. Concerned voters formed themselves into a “Citizens Protection Committee” was formed to resist this outrage. Questions were raised in The House of Commons and a public enquiry was held. In the end a compromise was reached, a suitably stately centre pole was designed specifically for Princes Street to appease the critics.

The Corporation didn’t hang about any further and forged ahead with impressive speed. The conversion of Princes Street from cable to electric was done in a single overnight shift, including erecting the entire pole and wire system and removing the cable apparatus. It took only 2 weeks to re-lay the entire north-side track 2 feet further out to allow the centre poles to fit in. Service was maintained throughout on a temporary track laid on top of the road surface

Leith Corporation – absorbed reluctantly into Edinburgh in 1920 – had taken matters into its own hands in 1904 and totally rebuilt its tram network into a modern, electric one. This had resulted in the “Pilrig Muddle”, where through passengers between Leith and Edinburgh had to swap from an Leith (electric) car onto an Edinburgh (cable) car at the municipal boundary at Pilrig Street. The opportunity therefore presented itself to unmuddle the muddle. There was a similar experience at Joppa, where onwards trips to Musselburgh moved onto the electric system of that district, but traffic here was less intense.

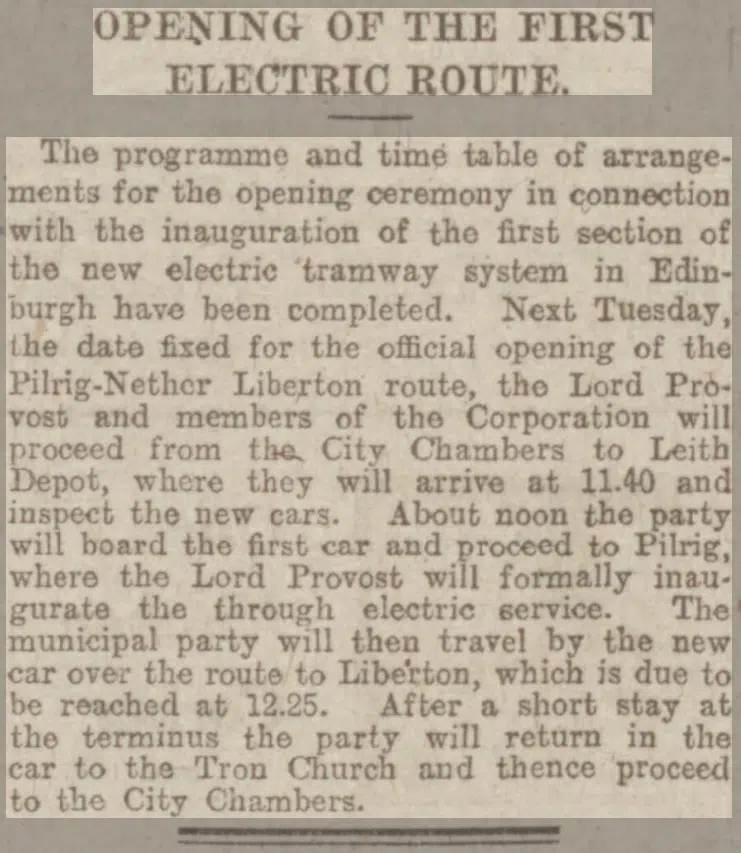

Work proceeded quickly to integrate the two networks, and the date of the first through tram was set for June 20th 1922. It would run from Leith to Liberton, and a Leith councillor remarked that he was “proud the first up-to-date tramcar in Edinburgh [was to start] from Leith“.

The Musselburgh News reported that “there was a natural curiosity and expectancy amongst thousands of citizens to see the public start of the new cars.” The first tram was to be driven out of Shrubhill Works by Lord Provost Hutchison, followed by a further 2 cars, “all gaily decorated“, containing the official party.

A blue ribbon was stretched across the road at the Edinburgh – Leith boundary at Pilrig to be cut. The Lord Provost handed over control of the tram to the driver at the G.P.O. at the top of Leith Street.

On crossing the Bridges and reaching the University the way was found blocked by the students who had formed a barrier across the road. This was an organised “rag”, a pretext for disorder and high-jinks. The student body was apparently aggrieved at having been excluded form the official proceedings. “Progress was impossible, and it was soon noticed that the young ” intellectuals ” were bent on sharing in the first trip”. When the trams came to a halt, they were pelted with flour bombs by the throng and hundreds of students attempted to get on board. Many of them managing to cling on to the outside of the cars and the sole police constable on duty could do nothing to prevent this.

The cars began to proceed again, intruders and all. Some of the students managed to climb onto the roof, helping themselves to the decorative flags and bunting for their own adornment. When the trams attempted to move on again, the students dislodged the current collection pole on the lead vehicle and the tram had to proceed to South Clerk Street under gravity alone, where it ground to a halt, powerless. The following crowd of students renewed their assault on the vehicles, having been able to summon fresh supplies of flour, meal and paper bags.

Restarting, the trams slowly began to outpace the following throng and an uneasy peace ensued between the official party and the intruders until Church Hill was reached, where the police under Chief Constable Ross were waiting. They managed to instil some discipline on the students but found they could not remove them, despite a direct appeal to them from the Lord Provost; “Now that you men have had what you were pleased to call your fun, which, I may tell you, has caused considerable discomfort and annoyance to this party, among whom is a lady, I would ask you now to leave the cars and enable us to proceed on our return journey in peace”. The Lord Provost was particularly aggrieved because his wife the Lady Provost had been hit in the face with a bag of flour. The Chief Constable telephoned headquarters for assistance.

At the destination in Liberton, a Corporation bus full of police reinforcements – driven by Councillor Thomson – had been sent ahead to ensure no repeat would happen on the return journey. The trams were met by the police, with batons drawn, and the students were forcibly ejected and sent packing. The return journey was undertaken with heavy police escort and at a speed sufficient to outpace the students who tried to follow by running.

The official party then returned to the City Chambers for a celebratory luncheon and speeches. The convenor of the Tramway Committee – Councillor Mancor – used his speech to make a thinly veiled attack on the “Citizens Protective Committee” who “seemed to think they were better informed of the wishes and desires of the constituents than the Town Council.” Mancor described the objectors to “Rip Van Winkles”.

The day ended on a down note when a car on Leith Street fouled the overhead wires and snapped them, bringing the network temporarily to a halt in this area, followed by a snap near Salisbury Place, again creating a temporary halt of service. These were the result of teething troubles, the overhead lines being strung too taut.

The Students Representative Council that evening issued a “manifesto” calling for restraint on the part of the student body but without actually apologising;

The unfortunate incident which occurred this morning , when a student was seriously injured , is being inquired into by the police authorities, who have expressed their regret , at the occurrence . The case of the students concerned is being adequately represented by a number of students who were eye-witnesses .

It will obviously damage the case and prejudice the general body of students if any further demonstrations are made . Unpleasantness between the police and students is to be deprecated at any time, particularly as the former have always treated student “rags” sympathetically .

It is now a long time since anything , like this has occurred and both students and policemen are apt to get excited with very little provocation . All students are therefore earnestly requested to refrain from any rash act which would bring the name of the University into disgrace

The rag this morning was on the whole quite a creditable performance and it would be a pity that it should be marred by subsequent thoughtlessness on the part of a few” The Scotsman – 21 June 1922

A procession of over two hundred students marched to the Empire Theatre in the evening where they applauded the performers before marching off in the direction of Princes Street before dispersing.

The cable and electric systems operated in parallel for a period, but the Corporation proceeded with full electrification at a breakneck speed. Princes Street was completed by 21st October 1922. The Comely Bank and Mound section was the last to be converted from cable haulage, “much to the disgust” of the polite classes of the New Town and Stockbridge. The system was fully electrified by the 8th June 1924, a remarkable achievement in almost exactly two years.

If you have found this useful, informative or amusing and would like to help contribute towards the running costs of my site (including keeping it ad-free) or to the book-buying budget, why not consider supporting me on ko-fi.