The Zeppelin raid on Edinburgh in 1916

This story began as a thread on my Twitter account @cocteautriplets.

I write threads on the more obscure or wacky bits of Edinburgh and Leith local history and Scottish modern history.

It was fittingly dark and late when I started to write this one, the story of the Zeppelin air raid on Edinburgh and Leith of 2-3 April 1916.

It’s a long-ish story which I’ll break down into three parts and will clarify a few points, adding some extra details to complement other tellings of it.

Part 1. Prelude

The frightening and fascinating new technology of Zeppelins burst quite literally into the British public consciousness on 19-20 January 1915 when an attack on Great Yarmouth, King’s Lynn and Sheringham left four dead and fifteen injured. Follow up raids are a failure, until bigger and more capable Zeppelins arrive and in April and May 1915 towns across the southeast of England from Ipswich to Dover are targeted and hit. Three are killed and there is public outrage.

Public and newspaper ire is directed as much at the authorities for failing to protect the populace and smite the aerial menace as much as at the German military. In September a Zeppelin humiliatingly appears with impunity over London. By the end of 1915, 203 people have been killed and a further 711 injured in monthly raids over (mainly) the Eastern and South Eastern counties of England.

The authorities have been largely impotent in response, but try to mobilise the public outrage as a recruiting tool.The Daily Mail is amongst popular newspapers which offer its loyal readers a compensation scheme should they or their family be killed or injured by a Zeppelin air raid. There are public awareness campaigns, warning people what to look out for when scouring the skies for aerial attackers.

In early 1916, during a winter lull in the bombing campaign, George Currie MP for the Leith Burghs asked the Scottish Secretary about what was to be done by local authorities to guard against the aerial threat.

A week later, the Secretary for Scotland, the Rt. Hon Thomas Mackinnon Wood, issues the “Lighting Order”, which obliges local authorities to implement a basic blackout and put in place warning measures of air raids, but leaves the details to local discretion.

A debate rages in Edinburgh Town Council about the best way to enact the order. The Chief Constable wants a complete night-time blackout but is felt to be over-reacting and over-stepping his authority. An audible warning is felt to be unnecessary and might just draw people out onto the street anyway. It is eventually settled that in the event of an air raid, the Corporation Electrical Department will dim the lighting supply as a warning before cutting it entirely as a blackout. However the gas lighting supply (the predominant domestic lighting) will not be dimmed or cut, over fears that it will lead to leaks from unlit lights when the supply is restarted. This means that there is no warning system in place for people who use gas lighting – the majority – and the blackout will not be effective. However this is accepted. After all, Edinburgh is very far away from it all and probably feels its isolation is protection enough. The burgh of Leith follows suit and issues similar orders, however these do not apply to the shipping sitting in Leith Roads and they continue to burn lights at night.

The air raids begin again at the end of January 1916 with the full moon; 57 are killed and 117 injured. There is respite as a result of the weather at the end of February but the Zeppelins return at the end of March. On the night of the 31st, 43 are killed and 66 wounded. But a Zeppelin is shot down during that raid, to public jubilation. On the next night (1-2 April), it is the North East of England that is hit, 16 people are killed and 100 are injured. The bombs are creeping northwards, but are still more than 100 miles from Edinburgh

Part 2. The Raid

On the bright spring morning of April 2nd 1916, the residents of Edinburgh open their morning newspapers to read headlines and horrifying details of the latest series of raids. Unknown to them, something sinister is stirring 500 miles to the east.

At the Nordholz naval air base north of Bremerhaven, the Imperial German Navy readies four of the latest P-class Zeppelins for a raid on Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, the base of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet – the most powerful fighting force on the high seas. In the early afternoon, Zeppelins L13, L14, L16 and L22 take off and begin their long voyage west. These 163m long, 4-engined craft have a crew of 19, cruise at 39mph, can reach an altitude of 11,600 feett and carry up to 2,000kg of bombs; high explosive and incendiary.

L13 soon develops engine troubles and turns for home. L14, L16 and L22 press on west, but are troubled by a northerly wind that blows them well off course. L16 makes for the secondary objective of Tyneside but drops her bombs 11 miles off target. L22 gets a bit lost and mistakes the river Tweed for the Tyne, bombing fields around Chirnside. She will later claim to have destroyed one of the bridges over the Tyne.

L14 – under the capable command of Lt. Commander Alois Bocker – is however on course and schedule. She passes the Scottish coast near St. Abb’s Head, being spotted here and possibly engaged by Royal Navy destroyers. Nevertheless, the alarm is now raised and the Admiralty dispatches the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron from Rosyth on a search of the Forth to look for the raider.

At East Fortune naval air base, Sub Lt. GA Cox is scrambled in an Avro 504C fighter on an ultimately fruitless interception mission. Cox will be injured later trying to land his rickety aircraft in the dark. And in Edinburgh and Leith, the warning message is received by the authorities that an air raid may be imminent, and the electric lights are dimmed and the tramway is stopped. The fire brigade, hospitals and Red Cross are put on alert.

Bocker turns L14 turn back out to sea after passing St. Abbs, using the Isle of May in the outer reaches of the Forth to get their bearings, then flying directly down the middle of the Firth. They appear over Inchkeith around 11:15PM. Over Inchkeith they do what Zeppelin attackers often do; they stop to take their bearings, floating high over the island. The night is clear but there is a low haze and they cannot make out their target from the glazed cabin high above the sea. Instead, the welcoming lights of the ships in Leith Roads point Bocker towards the docks and L14 sets off again with a new target in mind. Bocker is familiar with the port having visited it as a sailor in peacetime and he knows if he follows its river it will lead him to the city centre of Edinburgh.

The Leith Police spot L14 around 11:25, approaching from Inchkeith. She is flying high, perhaps as high as 10,000ft. The zeppelin (the black track on the below map) is heading southwest, straight towards the heart of Leith. The first three bombs are unleashed here. Bomb 1, a 50kg high explosive (HE), lands in the Edinburgh dock, sinks two rowing boats and destroys the skylight windows of a Danish sailing vessel

The two incendiaries, bombs 2 and 3, land near the Albert Dock but cause no damage beyond a burnt fence which is quickly extinguished. Bombs 4 and 5 are High Explosive. They hit a grain warehouse in the Timberbush and the Custom House Quay. Damage is done to property from flying masonry and smashed glass, but it’s largely superficial and nobody is hurt.

Bomb 6 is high explosive, it hits the roof of the tenement at 2 Commercial St. and takes L14‘s first victim; 61 year old engineer Robert Love- husband of Ann Porteous and father of James – is killed as he sleeps in his bed in the top floor flat. A few doors down at 14 Commercial Street, bomb 7 – an incendiary – smashes through the roof and then through the floor of the top floor flat before starting a fire in the flat below. The elderly woman who had been sleeping in her bed calmly got up and poured a pan of water in the hole and extinguished it.

More bombs rapidly drop. 8, 9 and 10 are incendiaries and land on Sandport Street. A fire is started and rapidly extinguished and no further damage is caused. Bomb 11 is another 50kg HE. It comes down in Innes & Grieve’s whisky bond on Ronaldson’s Wharf and sets the spirit store on fire. The inferno lights up the night sky, making the Zeppelin’s job easier. The entire stock, worth £44k (an enormous sum in 1916) is destroyed. It is not insured against aerial attack (this seems to be a recurrent situation at the time, special “air raid insurance” schemes were set up to cover where other insurance would not) . Bomb 12, an incendiary, lands at 15 Church St and falls through the roof into a room where a mother and 3 children are asleep. The flats are set on fire but the residents have a lucky escape before it is quenched.

Bocker now steers L14 along a course following the Water of Leith. A stick of four incendiary bombs is dropped around Mill lane. The St. Thomas Church manse is largely destroyed, but the minister and his family are miraculously unharmed. Clearly he had been saying his prayers as somehow he, his wife and their servant girl asleep in the attic were spared. The St Thomas’ School next door and the Leith Hospital across the street get lucky escapes as bombs 14 and 15 land directly outside. Bomb 16, landing on Hawthorn & Co’s shipyard, sets fire to a fence but it is quickly put out. L14 continues its course along the Water of Leith.

Four HE bombs are dropped over the industrial quarter of Bonnington. Seemingly little damage is done beyond smashed windows, but when the dust settles it is found that little David Robb, just one- year-old and who had been sleeping in his cot has been tragically killed by shrapnel. David’s parents, Robert and Jane, were just getting over the loss of another infant the previous year. The “disconsolate” Robert Robb gave an upsetting interview to a journalist that, unusually for the time, passed the censors.

L14 had now completed wreaking its terrible toll on Leith. Bocker took his bearings again from the Water of Leith and turned his ship to head south, directly towards the city centre of Edinburgh. It is 11.50pm. an HE bomb, number 21, is dropped, landing on waste ground at the end of Bellevue Terrace. It blows out windows in houses and flats for streets around and demolishes a tin shed, but no further damage is done. Likewise bomb 22, an incendiary, does no damage when it lands on the road surface of The Mound.

The Zeppelin’s course takes it just past the Castle atop its promontory. The next bomb, 23, is another 50kg HE. It crashes through the roof of the Georgian townhouse at 39 Lauriston Place. The McLaren family are awake inside and hear it descending on them. Dr Mclaren and his wife and teenage daughter miraculously are unharmed at 39 Lauriston Place, despite the damage. The family reputedly still have a piece of the bomb’s nose cap. The Skins – the Edinburgh Special School for children with ringworm – next door is also damaged. This bomb does claim a victim though. David Robertson, a 27-year-old soldier invalided out of the Royal Field Artillery, is outside in an adjacent street to see what is going on and is hit in the stomach by flying shrapnel, later succumbing to his injuries.

Bomb 24 is high explosive. It lands in the playground of George Watson’s College school and causes extensive damage to classrooms. It is perilously close to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh next door. Bomb 25 is an incendiary and lands near Jawbone Walk on the Meadows without causing damage. L14 continues south over the Meadows before making a turn to east, dropping bomb 26 – another 50kg HE – as it does so. This comes down in the tenement at 82 Marchmont Crescent. It fails to properly explode but its kinetic energy carries it through floors and ceilings to the ground floor flat at no. 80. It is this bomb that is now on display at the National Museum of Flight at East Fortune.

Meandering east across the Southside, incendiaries are dropped (bombs 27 and 29) at Hatton and Blacket Places, landing in gardens and doing no damage. An HE bomb comes down at 183 Causewayside and “practically wrecked” the tenement. Six are injured, four of whom are hospitalised. One of the injured, 71 year old Wilhelminha Henderson, will succumb to her injuries in the following days and dies in hospital of a heart attack brought on by the shock.

L14 now makes a U-turn back towards the city. This time it passes directly over the Royal Infirmary, dropping an incendiary (bomb 30) as it does so. This comes down on a roof but fails to do any damage. The incendiary bomb used at this time was a conical-shaped device with a central fuse. Inside the cone was a mix of oil and kerosene, on the outside it was wrapped in tar-soaked rope. It was not particularly effective. There are multiple eye-witness reports of seeing “blue lights” dropping from the Zeppelin. What people were seeing was the long streamers on the incendiary bomb’s tail, which were meant to stabilise it, catching the light as it fell. One of these incendiaries from the night is also on display at East Fortune.

The Zeppelin is now on a heading directly for the Castle. Another HE bomb – number 31 – is dropped, coming down in the Grassmarket outside the White Hart Hotel and Gothenburg tavern. Four men gathered in the area are injured and more damage is done to buildings. One of the injured, a 45 year Corporation Porter by the name of William Breakey, will die shortly afterwards from his injuries having been struck on the chest by flying debris. Most of the windows in the Grassmarket were blown out. Buildings took the scars of flying debris. Given how usually busy and how densely overpopulated the neighbourhood was, it was remarkable that the death and injury toll here was not much higher.

Bocker was perhaps aiming for the Castle (which he will fly almost directly over three times that night); bomb 31 at the Grassmarket and 32 and 33 – which fall immediately after – are in a straight line across it. Bomb 32 hits the southwest face of the Castle Rock. The Castle gunners impotently fire two blank rounds from the One O’Clock Gun in response. At the County Hotel on Lothian Road number 33 falls, an HE bomb, and there is another miraculous escape. The bomb explodes in the hotel roof causing extensive damage, but casualties are limited to a woman resident in a bedroom below suffering slight injuries .

Having missed the castle, L14 continues on its course before picking up its navigational maker of the Water of Leith again. Again a 180° turn is made, again bombs are unleashed as it does so. What Bocker is aiming for is anyone’s guess. Perhaps railways, perhaps the prominently large building of Donaldson’s Hospital. But all 3 bombs land in the river and although countless windows are blown out – including Donaldson’s chapel stained glass – there are no injuries. L14’s new course takes it back directly over the Castle again but this time no bombs are dropped; not until it is well past it at least.

Bomb 37, a high explosive, comes down outside the tenement at 16 Marshall Street off Nicolson Square. This will be the most deadly bomb. Residents had gathered in the passageway of the building, probably up and about due to the excitement of it all and taking shelter within as the drone of the Zeppelin’s engines approached again. The 50kg bomb strikes the pavement outside, the blast is driven into the stair of No. 16 and kills six men and boys standing within instantly. It injures a further seven. The victims are;

- William Smith 15;

- his father John Smith 41;

- Henry Rumble 17;

- David Graham 5;

- William Ewing 23;

- Victor MacFarlane.

The injured include the brother and son of the deceased Smiths and the father of Henry Rumble. Private Thomas Donoghue, 24, of the 3/4 Royal Scots who is home on leave was also injured. He had been visiting family and would succumb to serious injuries to the abdomen; the seventh fatality from Marshall Street.

The bomb at Marshall Street fell at about 12.25am, fully an hour after L14 was first spotted approaching Leith. And still it droned on over the city, at complete liberty to undertake its terrible deeds. As it continues on its course, two more HE bombs are dropped. 38 lands in the tenement at Haddon’s Court and 39 comes down in the tenement at 69 St. Leonard’s Hill. Each of these bombs will claim a victim. At Haddon’s Court, James Farquhar, a 73-year-old mason, will die five days later in hospital from his injuries. At St Leonard’s Hill, four-year-old Cora Edmond Bell is killed in her bed.

L14’s course takes it over the south western edge of the King’s Park. Here the City finally fights back, soldiers have been dispatched to the Salisbury Crags (where there was a military rifle range) and engage the Zeppelin with a Lewis and a Vickers machine gun. L14 drops four of its last five bombs, an incendiary and three HEs. It is perhaps aiming for the railway yard at St Leonard’s, or the flashes of gunfire far below, but no damage is done beyond to some walls and the gunners have no chance of hitting the Zeppelin anyway at its altitude. The last bomb, number 44, falls further south in the grounds of Prestonfield House at around 00:40AM (times in the records vary and conflict slightly). L14 now turns east around the south of Arthur’s Seat and strikes a course for home.

In the approximate hour and 15 minutes when it was over Edinburgh and Leith, it dropped 44 bombs, caused 14 fatalities and 24 injuries. No targets of any military value had been hit, a whisky bond and a manse had been destroyed, and countless thousands of window panes smashed.

Part 3. The Aftermath

It took until 4 April, the day after the morning after the raid, for the events in Edinburgh and Leith to hit the papers. Reporting censorship restrictions kept things vague and just referred to “south east Scottish counties” and “an eastern coastal town” . The Scotsman praised the public response “the raid… naturally caused some excitement, but failed to produce any panic or do otherwise than steel the hearts of the people against the nation capable of using such barbarous methods of warfare against the civilian population“.

The first three Funerals took place on the afternoon of 5 April. A further four Funerals took place on the 6th. Municipal representatives were present and there “were numerous manifestations of public sympathy as the cortège passed”. It was announced that the National Relief Fund had made “provisional arrangements” to give grants to local committees for the purchase of furniture for displaced persons. It was anticipated that applications would be made to the fund for indirect losses, for example loss of lodgers.

The lack of accurate reporting meant rumours and gossip was rife. The word on the street in Dundee was that the Scott Monument had been destroyed. Visitors from there to family in Edinburgh asked if they could please go and see the ruins? Unable to report the facts, the Scotsman settled for odd editorials, for instance extolling the virtues of traditional Scottish construction over suspect English ways:

“Scottish stone proved more resisting than English bricks; instead of the crumbling ruins of houses… the only evidence of the raid on the tough fabric of Scottish buildings was shattered windows and indentations on the walls. This first raid on the costs of Scotland has been a great triumph for the Scottish builder.”

And there was an even stranger one on how the general lack of public panic was some sort of proof evident of the racial and genetic purity of the people of Edinburgh and Leith.

The Lord Provost, who was in London on council business, met with John French, 1st Earl of Ypres and Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Forces to “explain to him the position of matters in connection with the raid”. French was reportedly “quite sympathetic.” Official sympathies were sent to Edinburgh and Leith from war-torn France.

And in the letters columns, recriminations were quick to come. Multiple organisations of the city worthies and self appointed committees of dignitaries wrote their opinions about what must be done. All that could be agreed was that something must be done. Given the woeful state of the anti-aircraft defences in the country, Mr Ralph Richardson wrote to suggest that local authorities must be empowered to raise their own air forces, as they did fire services “to defend the lives and property of the lieges committed to their care“. There was also the question of the warning and blackouts. It was ordered that the gas supply would be cut along with the electricity in the event of a raid. Stricter blackout conditions were made, to be “drastically enforced” due to the “slackness in various parts of the city”

In response, the Army provided a rudimentary anti-aircraft battery on Corstorphine Hill. Manned by artillery volunteers the gun was a QF 13pdr 6cwt Mk.I. This was a “marginally effective” weapon, and indeed was a cast off; only 20 had been made before being replaced by something better. This had likely been sent to Scotland as a token gesture to show that the military authorities were doing something, anything, in response. The battery was provided with a searchlight and an acoustic direction finder, which was meant to help locate the direction from which a Zeppelin was approaching from the noise of its engines (it didn’t really work). These defences were more morale-boosting “security theatre” than anything effective. However “War Weapons Week” campaigns in later years of the war encouraged the public in Edinburgh to directly finance better anti aircraft weapons to guard against the Zeppelin threat.

The proximity of the bombs to Edinburgh castle worried the governor, who wrote to the Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland to inform him that the Regalia of Scotland had been moved for safekeeping from the Crown Room to the Castle vaults.

At least two babies born just before or after the raid were named in its honour:

- Catherine O’May Campbell Raida Smith was born 2nd April to Janet Smith at 49 Montague Street

- Raida Alexandra Douglas was born May 21st to Barbara Mackay Douglas of 88 Nicholson Street

Raida Smith’s father, Peter, made an appeal against conscription on account of his wife “remaining ill… she did not make a good recovery and has been nervous and sleepless since… A strain that at present she is ill able to bear“. I don’t know if he was successful.

The L14 would become the most “successful” German Zeppelin of the War. It made 17 attacks on Britain and dropped 22 tonnes of bombs. Alois Bocker was shot down commanding L33 in September 1916 over London. He survived, was captured and reportedly treated well as a Prisoner of War.

Points to Clarify

There are many good accounts of this story, however there are various points and facts which have inevitably become confused or corrupted (with honest intention) over time. I will try to clear up those that I have identified.

Firstly, only one Zeppelin – L14 – bombed Edinburgh and Leith. L22 never made it and erroneous reports of it being over the city persist. German and British official records all agree that only L14 was within 100 miles of Edinburgh that night. L14 was much higher – 10,000ft – than you might think. It was dark and unlit, many people heard it, very few saw anything. As it flitted between pockets of cloud and light and went back and forth over the city it would be easy to think that you had seen or heard 2.

Secondly, there are no photos of L14 over the city. There are photos that purport to be it, but this is of the civilian airliner Graf Zeppelin over the city in 1930. There are other mockups too. But they are just that. Artists impressions printed in the London “illustrated papers” gave people a good idea what they might have looked like, but flying at an altitude of 10,000 feet, the public would have required a good set of binoculars or a telescope.

The third point concerns the number of bombs and fatalities.

- 20 bombs were dropped in Leith and 24 in Edinburgh. There are Police reports from each burgh’s constabulary that provide accurate details. Leith was however a separate burgh at this time and some accounts overlook this nuance and thus get the total wrong.

- 14 people lost their lives in total; some reports miss out some of those who died of their injuries up to 5 days later, they are listed in the table below

| Name and Age | Location | Name and Age | Location |

| Robert Love, 61 | Commercial Street, Leith | David Robb, 1 | Bonnington Road, Leith |

| David Robertson, 27 | Graham Street , Lauriston | William Breakey, 45 | Grassmarket |

| William Smith, 15 | Marshall Street | ||

| Henry Rumble 17 | Marshall Street | John Smith, 41 | Marshall Street |

| Victor MacFarlane | Marshall Street | William Ewing 23 | Marshall Street |

| Pvt. Thomas Donoghue | Marshall Street | Wilhelmina Henderson, 71 | Causewayside |

| James Farquhar, 73 | Haddon’s Court | Cora Edmond Bell, 4 | St. Leonard’s Hill |

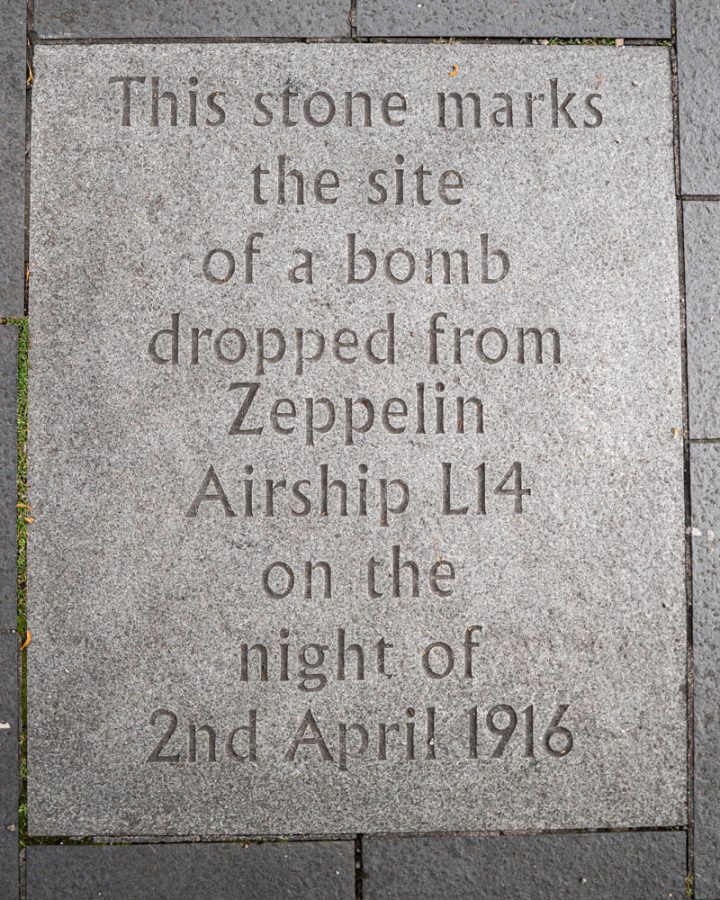

As far as I’m aware, there are 3 public memorials to the air raid.

- A flagstone on the Grassmarket where William Breakey was fatally wounded.

- A piece of damaged masonry from the old Grassmarket Corn Exchange, now removed to the back of the Apex Hotel car park with a descriptive plaque

- A plaque on the Castle Rock, near where the bomb fell there. There is a picture on this site;

And there are two bombs on display at the National Museum of Flight at East Linton.

The events of this night were commemorated back in 2016 but still don’t really pervade the local public consciousness, at least not to the extent of the attacks made during WW2.

And for other stories like this have a look at my website here.