Edinburgh woman’s death – the first modern murder

It was one of the most sensational murder trials of the 20th century.

If it had not been for the combined brilliance of three Scottish scientists and a battle-hardened police officer, Dr Buck Ruxton may have escaped the gallows.

Ruxton was a charismatic doctor working as a GP in Lancaster when he attacked and killed his Edinburgh-born wife Isabella and her maid Mary Rogerson. The skills learned when he tried but failed to become a surgeon, meant Ruxton was able to expertly dismember and disfigure the bodies, in the hope that even if they were found, it would be impossible to establish their identity.

Later he drove 100 miles north to Moffat in the Scottish Borders and disposed of 43 pieces of rotten flesh and bone wrapped in rags and newspaper, calculating that in a different country with a different policing and legal system, that it would improve his chances of avoiding detection.

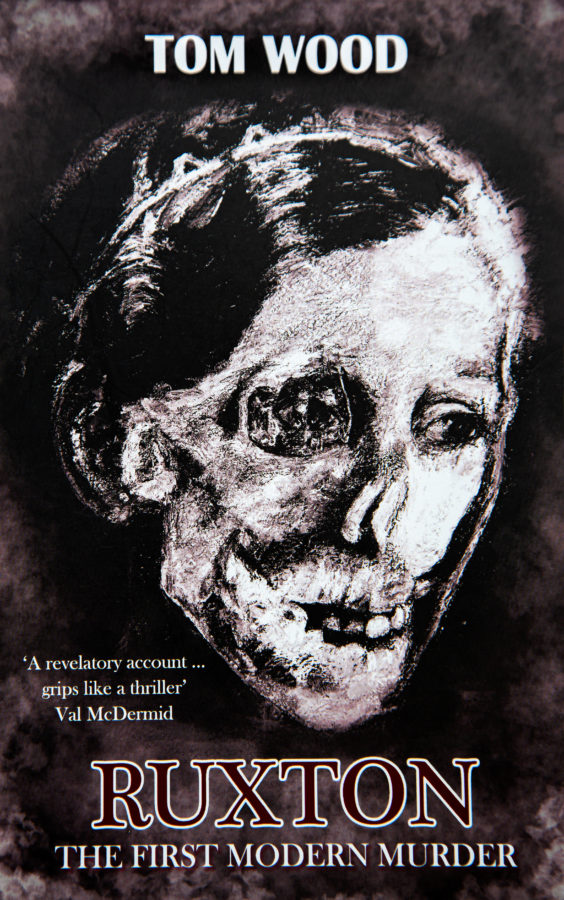

-

Killer Dr Buck Ruxton -

Ruxton’s victim wife Isabella

The gruesome murders attracted worldwide attention, with the public following every gory detail, and indeed Ruxton’s trial at the Assize Court in Manchester in 1936 attracted more than 50 international newspaper correspondents and was the first trial in the world to have its own media centre.

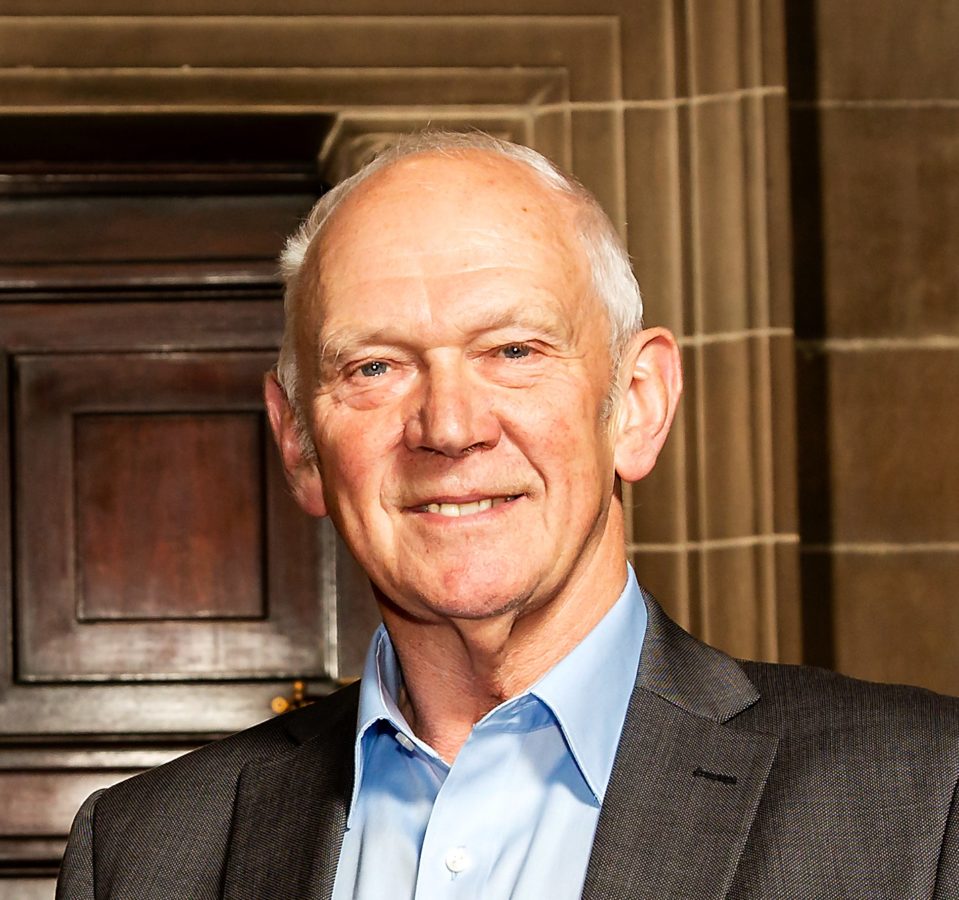

Now, former police chief Tom Wood, has recounted the extraordinary case in his book Ruxton: The First Modern Murder – establishing that many of the ground breaking techniques then deployed by police and scientists, laid the foundations for the future of scientific criminal investigations, many of which remain in common use today.

Tom said: “Eighty five years ago a crime committed in Lancaster had world-changing consequences and was solved by a very ordinary Scottish police sergeant and three of the most brilliant forensic scientists of the 20th century who, in an incredible coincidence, happened to be working at Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities at that time.”

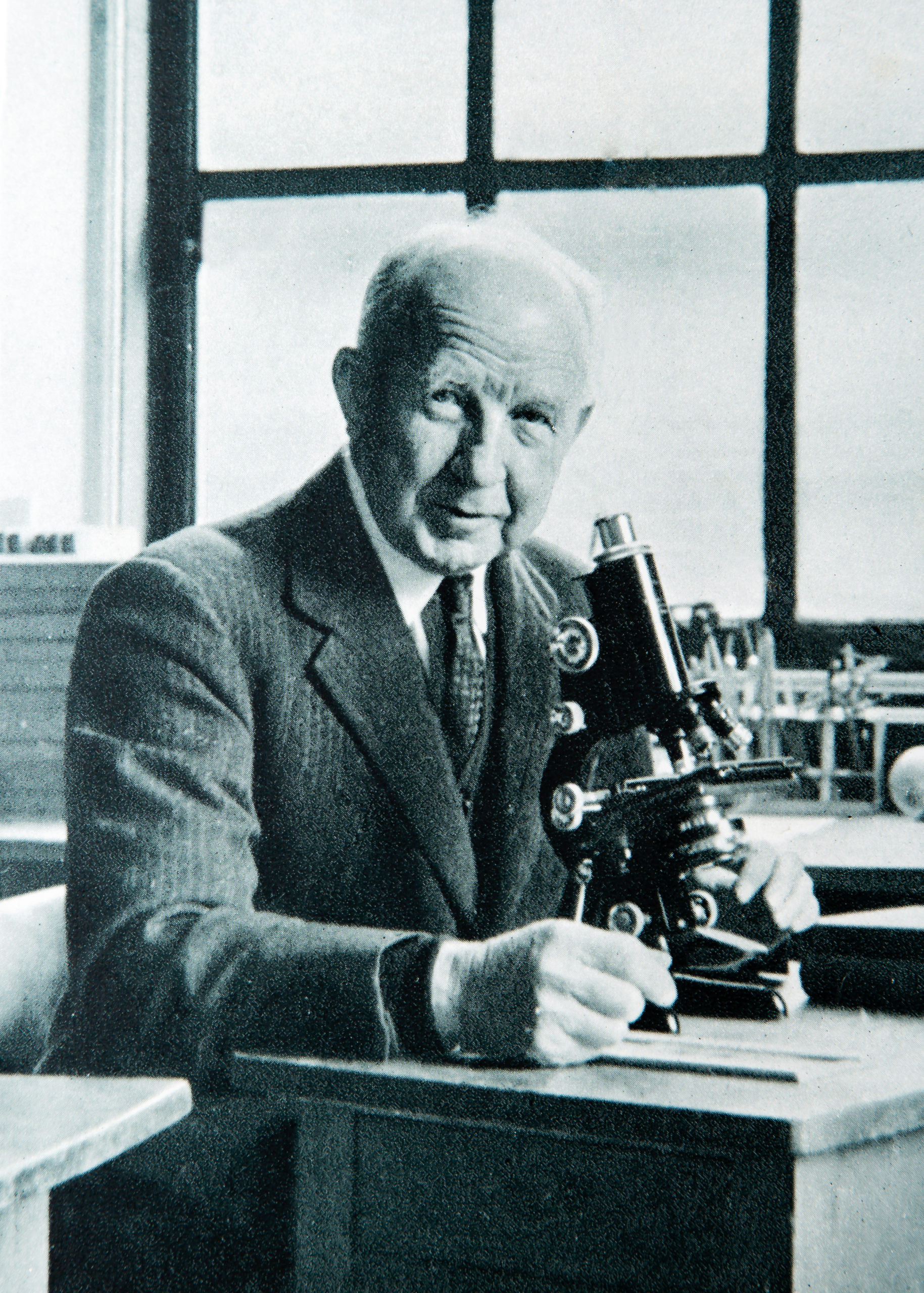

The four men were Sergeant Robert Sloan, the officer in charge of Dumfriesshire Constabulary’s station in Moffat, who crucially did something that had never been done before – preserved and guarded the crime scene as best he could. The scientific experts were John Glaister, Professor of Forensic Medicine at Glasgow University, James Brash, Professor of Anatomy at Edinburgh University, and his colleague Sydney Smith, Professor of Forensic Medicine at Edinburgh.

-

Professor John Glaister -

Professor James Brash -

Professor Sydney Smith

“The Ruxton murders have been remembered for their brutality, the fact the bodies were cut up, and for the forensic evidence which led to Dr Buck Ruxton’s convicion and execution, but this completely misunderstands the nature of these crimes. The real legacy of this case and what it should be remember for is the aftermath, and the fact the forensic approach to this crime gained so much kudos and credibility.

“The Ruxton case was a fault line. Before 1935 and these murders, criminal investigation was somewhat in the dark ages, it hadn’t really moved on much from the original Whitechapel Ripper times of 1881.

-

Hard as nails – Sergeant Robert Sloan

“Post Ruxton we moved in to the modern era that I worked in, where you had dedicated scenes of crime procedures, crime scene photography, fingerprints, and regional forensic laboratories were set up by each police force. The lessons learned from Ruxton were that influential, that it literally changed the way in which serious crimes were investigated in the modern era, and so it really was the world’s first modern murder.”

According to Wood, Dr Ruxton’s idea was a good one – let the body parts putrefy and then spread them across a wide area, where he thought wild animals would finish the job for him. Even if the remains were found, Ruxton believed they would not be identified as human or be able to be traced to a specific human.

“He did a very good job with limited resources of disguising the body parts,” said Wood. “It was not a fanciful thing that if he dumped the body parts over the border in Scotland, that liaison issues between Scottish and English forces would mean the case would fall between the cracks.

“Where he was really unlucky was that it was Sergeant Robert Sloan who first attended the scene of the crime. He had no experience whatsoever of a criminal investigation, no equipment apart from a torch, a notebook and a pencil. Yet following his common sense, the way Sloan performed in preserving the crime scene so that scientists could follow behind him, was completely exceptional.”

Not to detract from the significant contributions from Brash and Smith, it is John Glaister who Tom Wood picks out as the central character, along with Robert Sloan, as being crucial to ensuring Ruxton would pay the price of his horrendous crime.

“John Glaister could not have carried out the incredible work he did without Sloan, and Sloan’s work would have been completely wasted had John Glaister not been around to carry it on to trial.

“Glaister attended the scene and he is the first person in the world to have the vision that a holistic approach should be adopted for a crime scene. He ordered that samples of flora and fauna, soil, maggots, flies and other important evidence was removed from the crime scene to Moffat and thereafter to Edinburgh for forensic examination. This was revolutionary at the time – and it is exactly the way we do things now when a serious crime has been committed.”

In a criminal trial with so many “firsts” it should not be overlooked that James Brash was the anatomist who put the body parts together and who pioneered facial superimposition – and the first man to bring this technique to a court of law.

Tom Wood added: “I really object to the ‘great detective’ theory which comes from the pages of Sherlock Holmes and portrays the brilliant individual who cracks the case. In reality, and true to the Buxton case and every case I worked on as a CID officer, a crime is always solved by teams of people contributing their different but complementary skills sets.”

Another thread in Tom Wood’s book and which he believes unites the main characters, and which was important in bringing Buxton to justice, was that scientists and many of the police officers working on the case had served and survived the brutal and bloody years of the First World War.

He said: “The anatomists, as Glaister, Brash and Smith were known, and Robert Sloan had all served in the Great War. This united the scientists, Robert Sloan and indeed other police officers on the inquiry who had served on the Western Front and endured many hardships.

“Robert Sloan was as hard as nails, he served for two years in the Scots Guards and was hard physically and hard psychologically. Many people would have been freaked out by what he found by a quiet woodland in Moffat, but he had witnessed many horrific scenes in France and he was not phased by Dr Buck Ruxton’s evil work.

“He was the sergeant in charge of Moffat and he was going to do his job properly and I am convinced the discipline he learned in the Scots Guards and the sights he saw, shaped how he reacted on the day that the body parts were discovered by a young couple out for a Sunday morning walk.”

Tom’s research put him in touch with Robert Sloan’s family, who were unaware of the full contribution their grandfather and great grandfather made to one of England – and Scotland’s – most important criminal cases.

He said: “During my research in Dumfries and Galloway I met Robert Sloan’s grandson and other family members. Sadly, Robert Sloan died aged 44 from stomach issues which were a consequence of his service in the First World War.

“While his family knew he was involved in the Ruxton case they did not know what he had done or how important his contribution had been in solving the case, so the revelations in my book were a surprise to them all. Later I received a letter from Sergeant Sloan’s grandson saying the family were delighted to find out about how the grandfather they never knew had helped shape modern criminal investigations.”