At The Queen’s Gallery – Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing

Artists’ sketchbooks are frequently more interesting than the finished product. Preparatory drawings and notes give us a fascinating insight into inspirations, thoughts and ideas, and how these have been developed over time.

And if that artist is one of the most famous in the world, with interests in everything from painting to botany, architecture, ballistics, cartography, anatomy, engineering, and even water-powered clocks, the sketches and designs become an in-depth study of a remarkable, razor sharp, mind. Leonardo da Vinci – A Life in Drawing, a new exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Holyroodhouse, is a marvellous catalogue of the works of this quintessential Renaissance Man.

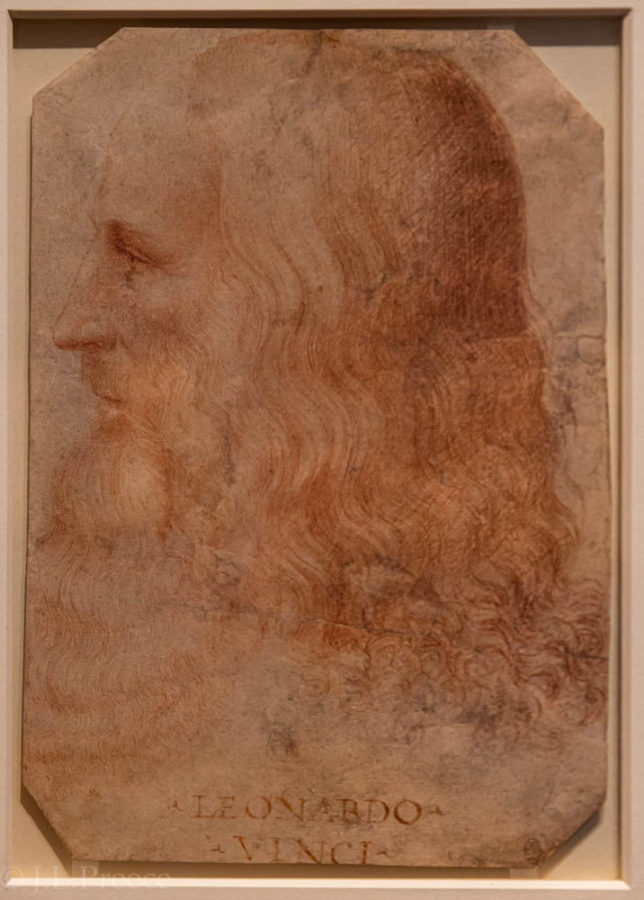

Born to an unmarried peasant girl in Tuscany in 1452, Leonardo had only an informal early education until his father’s family moved to Florence and he joined the workshop of Verrocchio, a leading painter and sculptor, where he learned the techniques and theory of art. (Botticelli and Ghirlandaio also worked there.)

Verrochio’s employees did a lot of his painting for him, and it is said that when the master saw how good Leonardo’s section of The Baptism of Christ was, he gave up painting altogether. Whether or not this is true, the drawings in this exhibition may well induce similar feelings of inadequacy in the viewer; Leonardo is simply one of – if not the – best.

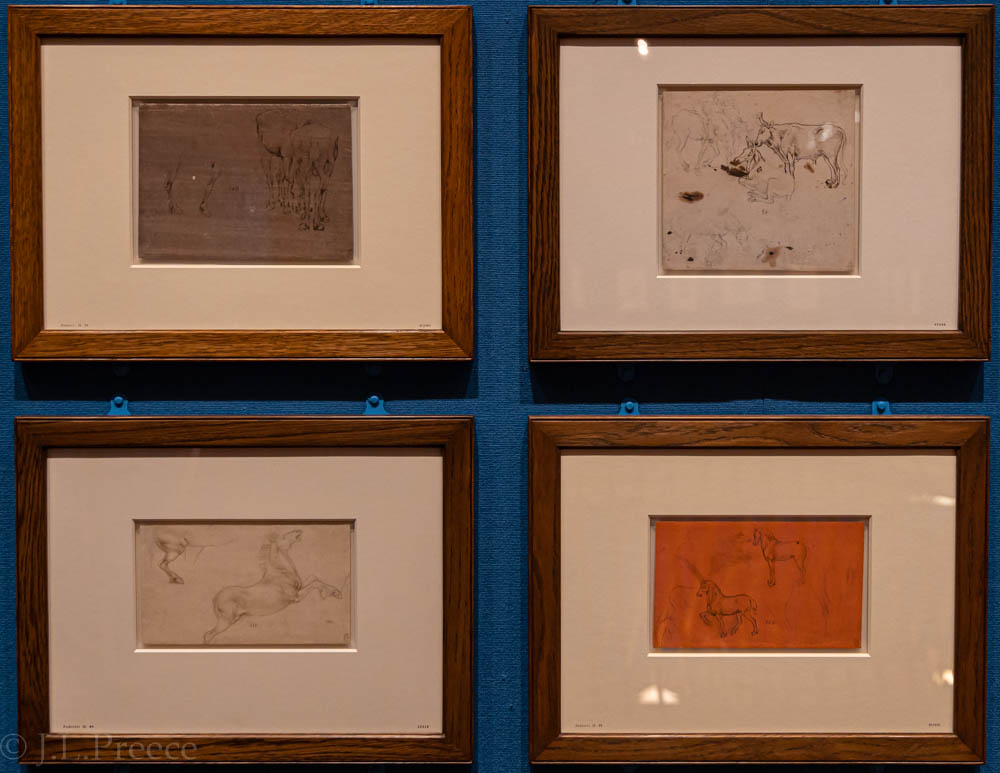

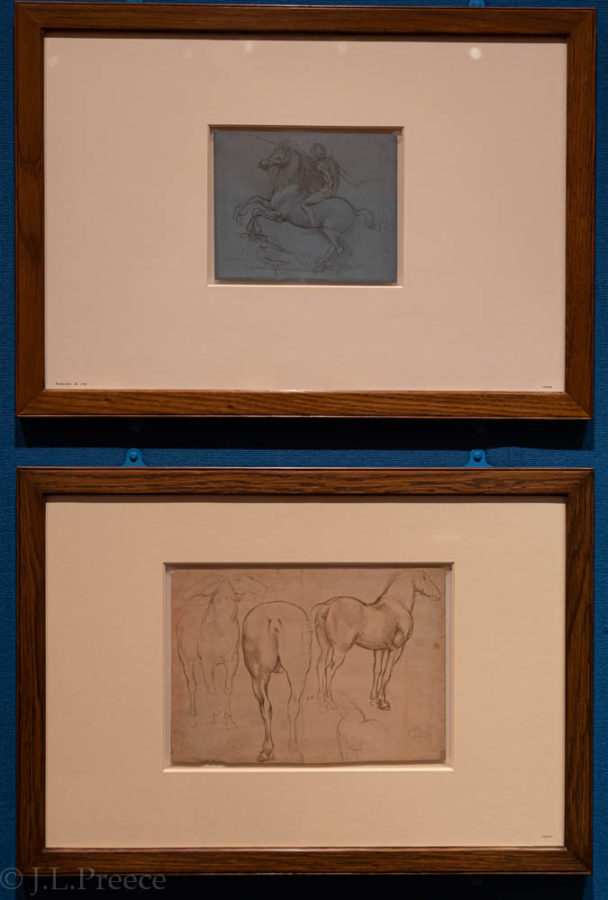

The works are arranged according to various periods of the artist’s career. In ‘Florence and Milan to 1499’ Leonardo’s studies of horses are particularly fine, with each position – standing, lying, rearing – perfectly captured. Leonardo drew horses throughout his life, both as pictures in their own right and as sketches for larger paintings, many never completed or lost. In one drawing, of a horse’s left foreleg, precise measurements are given, technical details being of great importance; in another we are faced with an extremely lifelike rear end.

-

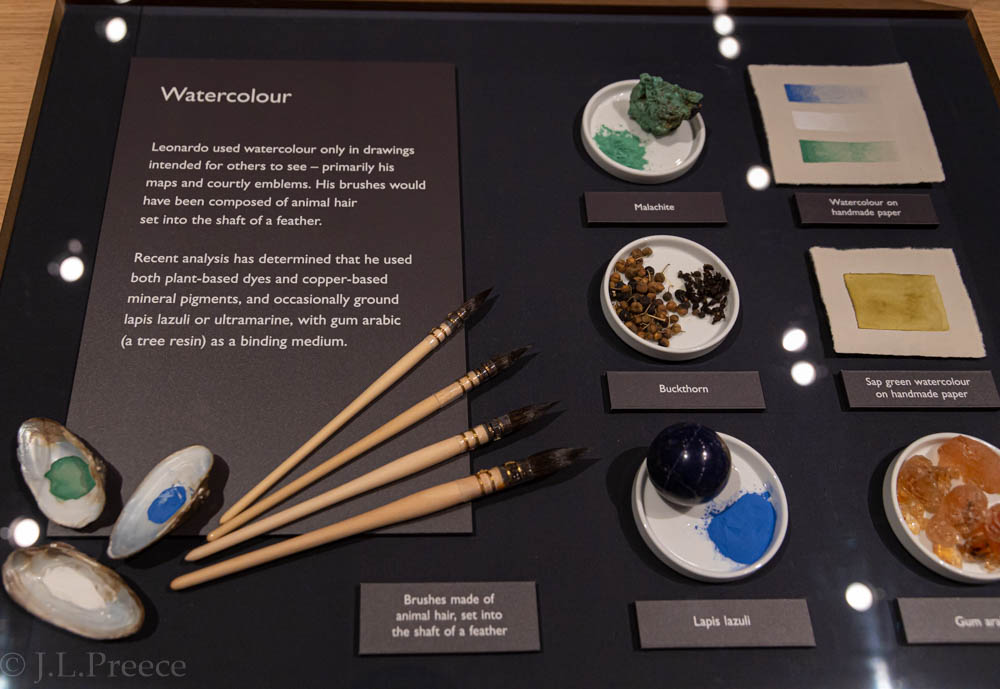

Watercolour Equipment and Pigments PHOTO John Preece -

Detail of Feather Quills PHOTO John Preece

Other drawings of this time include a portrait of a woman in profile, the delicate strands of her hair, escaping from her cap, almost tangible, and a picture of an ugly old man with jutting chin and angry expression, facing an old woman (who also looks quite masculine). Leonardo was fascinated not only by beauty – he was said (by his pupil Francesco Melzi) to be beautiful himself, with well-kept hair and a love of fine clothes – but also by the grotesque.

Leonardo left Florence for Milan and was soon working for its ruler, Ludovico Sforza. Before long his skill in drawing horses was needed again; he spent five years working on the design for a huge equestrian monument to Sforza’s father – a work that, like so many of his projects, never came to fruition, as when war was threatened the bronze was requisitioned to make artillery, and five years later Sforza was overthrown by the invading French.

The invaders also destroyed Leonardo’s clay working model: ten years later their commander, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, ordered another statue as a monument to himself, but although a sketch survives, this one didn’t even make it into clay, much less bronze.

While in Milan Leonardo made many studies of military equipment, arsenals, and ideas for new machines (few, if any, of which were ever made). In A Scene in an Arsenal the men struggling with a huge winch appear tiny, Lilliputian even, but they are still finely detailed and real. Leonardo’s designs for gun barrels and mortars show his interest in technical drawing and devices.

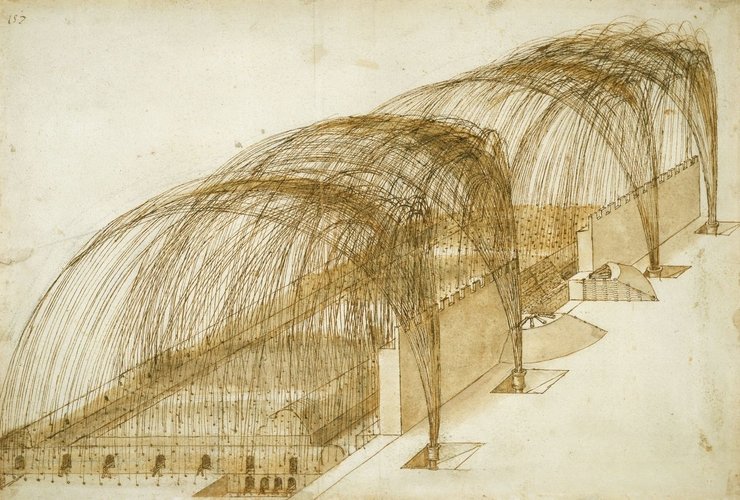

After a brief return to Florence he began working as a military surveyor for the head of the Papal army, Cesare Borgia, so many of these drawings probably had a practical purpose. His Studies of Casting Apparatus show more highly detailed drawing, and as ever he adds copious notes in his precise backwards writing – he was lefthanded and it is possible that he wrote backwards to avoid smudging the ink. Mortars Firing into a Fortress explains how the curtain wall could be breached by mortar fire – but the lines are so finely drawn that we could be looking at water fountains or huge, sweeping palm trees.

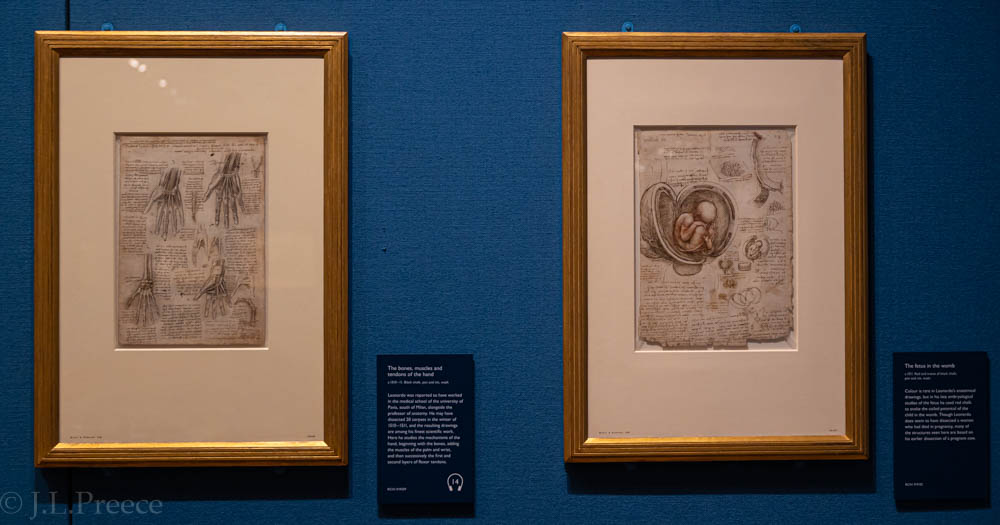

Working between Florence and Milan, Leonardo became increasingly interested in anatomy and botany. He had already drawn The Major Organs and Vessels, though this was based entirely on traditional beliefs about the relationship between organs; eventually he dissected thirty bodies (with no refrigeration or even any embalming facilities) in his attempts to understand how things worked. He sawed open a skull and drew that (The Skull Sectioned), and for his moving picture of The fetus in the womb he cut open the corpse of a pregnant woman.

The womb, like a nutshell, delicately holds the unborn child with its tiny feet and toes. Later in Leonardo’s life came drawings of the vessels of the liver and lungs – the latter with ribs meticulously drawn around them. A drawing of the bones, muscles and tendons of the hand shows the hand turning, the better to show how everything was thought to work. Leonardo didn’t get everything right – owing to a lack of bodies (especially female ones) he sometimes used animal organs and tried to adapt his drawings to what he believed were the human equivalents – but in many areas he was way ahead of contemporaneous knowledge.

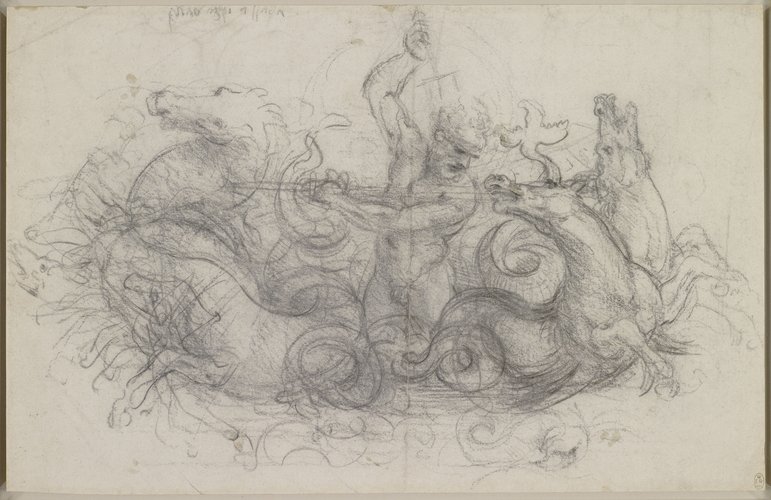

A drawing of Neptune – a sketch for a later painting, again lost – shows the sea god’s horses plunging furiously, the flailing of their legs conveyed by many overlapping outlines, their faces especially vivid, alive. Neptune’s tail waves above them. Leonardo drew this while working on sketches for The Battle of Anghiari, a mural commissioned by the Florentine government (but now lost and known only through a copy made by Rubens), in which horses were seen in similar agitated state. Another preparatory sketch includes a lion’s head.

The mural was intended to decorate one wall of the Salone dei Cinquecento, with Michelangelo being employed to paint the opposite wall – another work doomed to remain unfinished. Around the same time, Leonardo was possibly also working on a picture of Lisa del Giocondo, the model for the Mona Lisa. The sheer number of things Leonardo had on the go at once is presumably due, in part at least, to his need to make money, but also, more importantly, to his numerous interests and unstoppable imagination. One does wonder if his seething brain ever allowed him to take a day off.

To gain Cesare Borgia’s patronage, Leonardo made a map of Borgia’s stronghold, Imola. Maps were a new concept, and this one – which he made by pacing the streets himself – got him the job. After leaving Borgia’s service, he continued to make maps, some based on surveys, others on what he thought were good ideas, such as his proposal to build a canal to bypass the Arno’s rapids west of Florence. While the map of Imola is precise and clear, the canal plan is full of shading and squiggles. The idea was never developed.

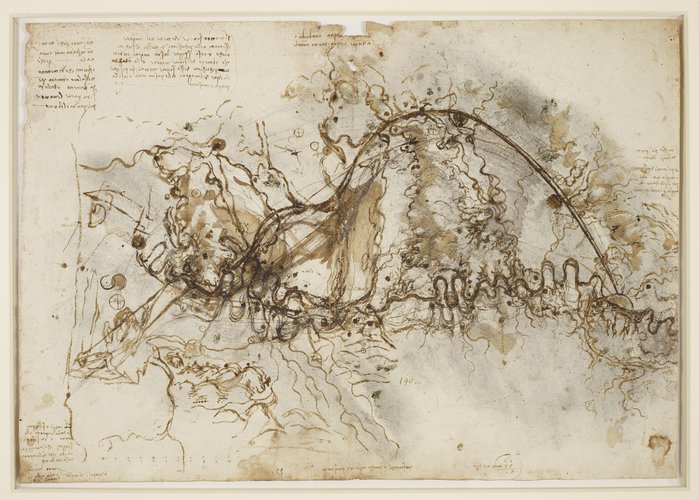

Between 1506 and 1512 Leonardo further developed his interests in plants, astronomy, and the properties of water. He made detailed sketches of blackberry sprigs, guelder roses and bur-reed, but became increasingly concerned first with the best way to draw water and then, as his health deteriorated, with deluges, floods and scenes of the apocalypse. A tempest, drawn between 1513 and 1518, shows tiny men and horses cowering on the ground as thunderbolts strike; even at this stage Leonardo must have had eyesight sufficient to cope with small detail, and the detachment to write copious scientific notes about mountains collapsing, rivers overflowing, the world being swept away. Around this time, however, he appears to have become incapacitated by a series of strokes.

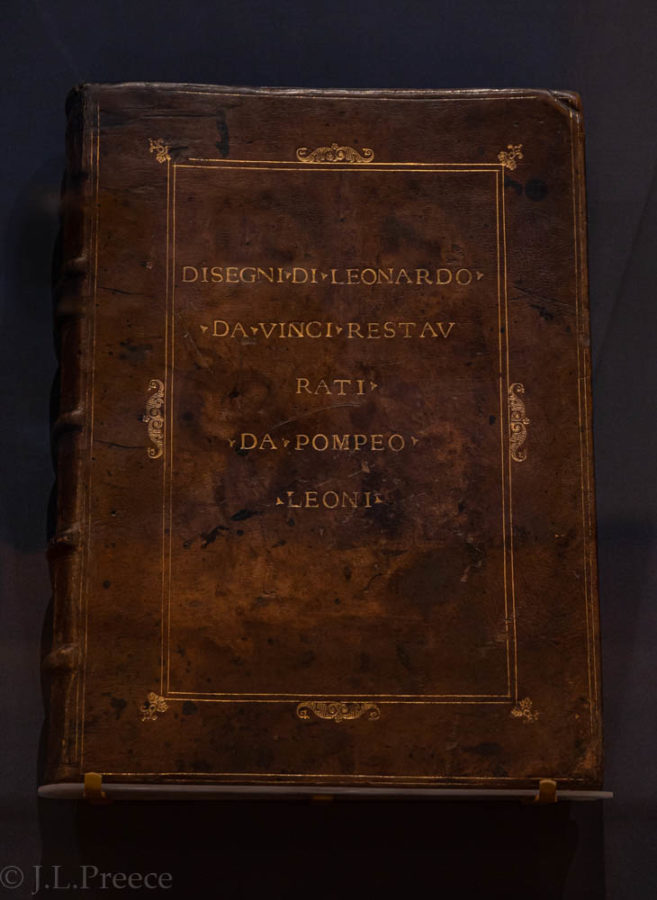

Having moved to France in 1516 to work for the King Francis I, Leonardo died at Clois Luce, his manor house near the King’s residence at the Chateau d’Amboise, in 1519. He had planned so many things, but, owing sometimes to outside events (in particular the numerous wars that took place during his lifetime), sometimes to his own perfectionism, few had been realised. He had, however, preserved all of his papers and notebooks, which were left to Francesco Melzi and later acquired by a sculptor, Pompeo Leoni, who stuck them into two albums.

By 1639 one album had been acquired by Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and by 1670 it was in the collection of Charles II. At the beginning of the 20th century the drawings were for some reason taken out and stamped with the cipher of Edward VII, but the leather album itself survives, and is on display in this exhibition.

Leonardo da Vinci A Life in Drawing is at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, until 15 March 2020. For opening times and ticket prices CLICK HERE

A book, Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing by Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings, Royal Collection Trust, is published by the Trust and available from RCT shops or online.