Edinburgh International Book Festival 2019 : How To Be A Writer For Life

Lauren James is only 27 but she’s already a highly successful author. Her books include The Quiet at the End of the World, The Starlight Watchmakers and The Loneliest Girl in the Universe. She sold the rights to her debut novel The Next Together while she was still at university – and where she studied not English but Chemistry and Physics.

David Almond’s writing career took a little longer to get off the ground – his breakthrough novel Skellig was published in 1998, when he was 47 years-old, though he’d had some success with short stories before that. Skellig won both the Carnegie Medal and the international Hans Christian Andersen Award, and since then Almond has been unstoppable, writing many more novels, plays, picture books, graphic novels – even opera librettos and songs – over the past 20 years.

On Friday at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, joint chairs Justin Davies and Elizabeth Frattaroli (both local Network Organisers for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) asked both authors, Lauren James and David Almond, about their careers, and what advice they could give to young people setting out on what they hoped might be a lifelong writing career.

James started to write for fun, as a break from all those numbers and symbols – but she’s still hugely committed to science, and particularly to women in science. All of her novels feature them and the book that most inspired her was Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights – ‘it had a woman scientist with her own amazing lab at Oxford University – and magic too.’ The Next Together grew from an idea she had at school about two time travellers who aren’t aware of their powers. She’d written 150,000 words by the time she reached her second undergraduate year – and she thought every one of them was brilliant. An editor took her in hand, pointed out that her jokes didn’t make sense and her plot lines went nowhere, and taught her how to edit. After that she had two offers in the space of two weeks. At the time she thought the wait interminable..

Almond wanted to be a writer for as long as he can remember. He grew up in a large Catholic family at Felling on Tyne, received no encouragement from his secondary school, but he wrote anyway ‘for the love of it’ and won a place at the University of East Anglia. His first novel was universally rejected, as were several more including a collection of short stories about his childhood. He had no plans to write a children’s book, but one day, as he was walking along the street, the idea for Skellig came to him fully formed;

I knew it was new and rich and very bright.

So now they’re both best sellers, what, asks Davies, do Almond and James do to keep going? Even they can’t rely on the books alone.

James has made a list of all the things she does that aren’t writing. It’s so long I give up trying to write it down halfway through, but it includes teaching (at Cambridge University’s Institute of Continuing Education and at the University of Coventry), freelance journalism, a monthly creative writing group for children, online mentoring and lots, lots more.

Almond says it’s important to diversify, not only to avoid putting all your financial eggs in one basket but also to keep yourself out in the world, to find new ideas, and to stop yourself getting bored. He relishes all forms of storytelling, works with artists and musicians, and has recently been involved in a stage show, which he loved. James started writing full-time as soon as she graduated, giving herself 7 years to see if she could succeed; by contrast Almond has had all sorts of jobs – teacher (‘6 weeks’ holidays to write in’), postman (‘I could write every afternoon, then I realised I’d have to get up at 4am), salesman, porter, labourer. He would write, he says, even if he had no readers and had never sold anything;

I can’t imagine what else I’d do. You do it because you want to make art, not money. If you do find readers you are going to share your art with humanity.

If James hadn’t beaten (by a long margin!) her 7 year deadline, she would have given it up and got a ‘proper job’, although she would have carried on reading and reading, and perhaps found her way back to writing one day.

The key to keeping going with your writing, successful or not, is obvious, said Almond.

You write. You keep on writing. Don’t tell yourself the type of writer you are too early. Be brave about what you write, and just keep on going.’

James’s advice is to have many projects on the go at once, all at different stages; don’t fix all your hopes on one manuscript. Both agree that it’s important to learn to accept rejection (James also stresses the importance of asking for feedback, and acting on it.). Almond: ‘You do need to be dogged, thick-skinned and stupid at times.’ They both still have moments of self-doubt, but say you also need to trust yourself, to ‘mute the negative voice inside’ (James). And Almond again;

People will tell you you can’t do things; you can. Why not try to be as good as Shakespeare? You should always be excited by what you’re writing.

Almond believes that we all come into this world knowing how stories work.

James and Almond both write about big themes; love, death, climate change. Young readers, says Almond, are fascinated by the big things. For James it was simply a matter of writing about what she wanted to read about, which was fundamentally the future of humanity, ‘my everyday thoughts’. Neither writer would avoid a topic as too controversial or dangerous; young people, James says, can handle anything if it’s dealt with in the right way. She would not write from the point of view of a member of a minority group, because she doesn’t think it’s appropriate for her to tell their stories, but she would certainly include such characters in her books.

The North East of England permeates most of Almond’s writing. He’s been told in the past that this will limit his readership, especially when he writes in the local, working-class dialect of his childhood. He’s found the opposite to be true. It’s only some British adults who have a problem with his style – children don’t, and neither does the all-important American market, which even lapped up a book he wrote in phonetic Geordie. Americans, he says, are used to regional voices. He has no time for the criticism that there are too many working class voices in modern literature;

It’s showing that something ordinary can be extraordinary.

Should authors tailor their books to make them relevant to each new generation of readers? Almond says definitely not. No-one ever mentions that there’s not a TV in Skellig, let alone a mobile phone.

Kids are always kids. The drama of growing up is the same everywhere.

James says it’s hard to know who readers of YA literature are anyway as many are adults. She writes for herself, but wonders if her writing will change with her own reading interests. She’s recently had the new experience of writing with Barrington Stoke, publishers who specialise in books for young people with dyslexia or visual stress, or who are simply reluctant readers. They use dyslexia-friendly fonts, special paper with no shadowing, wider spaces and no complicated words; James found this immensely interesting and says it taught her many things that she will apply to her mainstream writing – in particular, the importance of keeping your readers immersed in the story, of not ‘jolting them out of it.’

Both writers are keen supporters of libraries; as a child James used her entire family’s cards to borrow as many books as possible every week, Almond loved his local library and says he wouldn’t be the writer he is today without it.

Libraries are essential to our civilisation.

David Almond

Libraries give people the freedom to follow their own interests, explore their obsessions, and find things they didn’t know they were looking for. And it’s reading that James recommends to all aspiring writers;

Read everything and steal all the best bits.

Lauren James

All ideas have already been used, she says; what you need to do is put a different twist on them.

Almond is a fan of notebooks; he advises people just to start writing without thinking too much, to release the muse. He draws in a sketchbook and gets ideas from that too.

In the act of drawing and scribbling words you discover what your story is. It’s really weird and wonderful.

The usual advice to discuss drafts with other writers or groups doesn’t resonate for him. He didn’t share anything for many years; for him it’s a private thing.

James’s books are often about war, loss, the end of times. Is she, asks Davies, pessimistic about the future – will she even have a place to write in ten years’ time? In fact the opposite proves to be true; James is very optimistic. Technology is not, she says, a bad thing; it can be used in a good way, and that’s what’s important. She believes that the future is bright for the next generation; they will have amazing new areas to write about and explore.

I believe in the good of humanity; we will work together, it may take a long time, but we will survive.

Lauren James

This was an excellent hour with two brilliant, generous, thoughtful writers. Aspiring authors will have gone away enlightened, exhilarated and enthused. For, as Almond concludes.

Writing is about going somewhere that really matters. It’s about what it means to be human, to be alive.

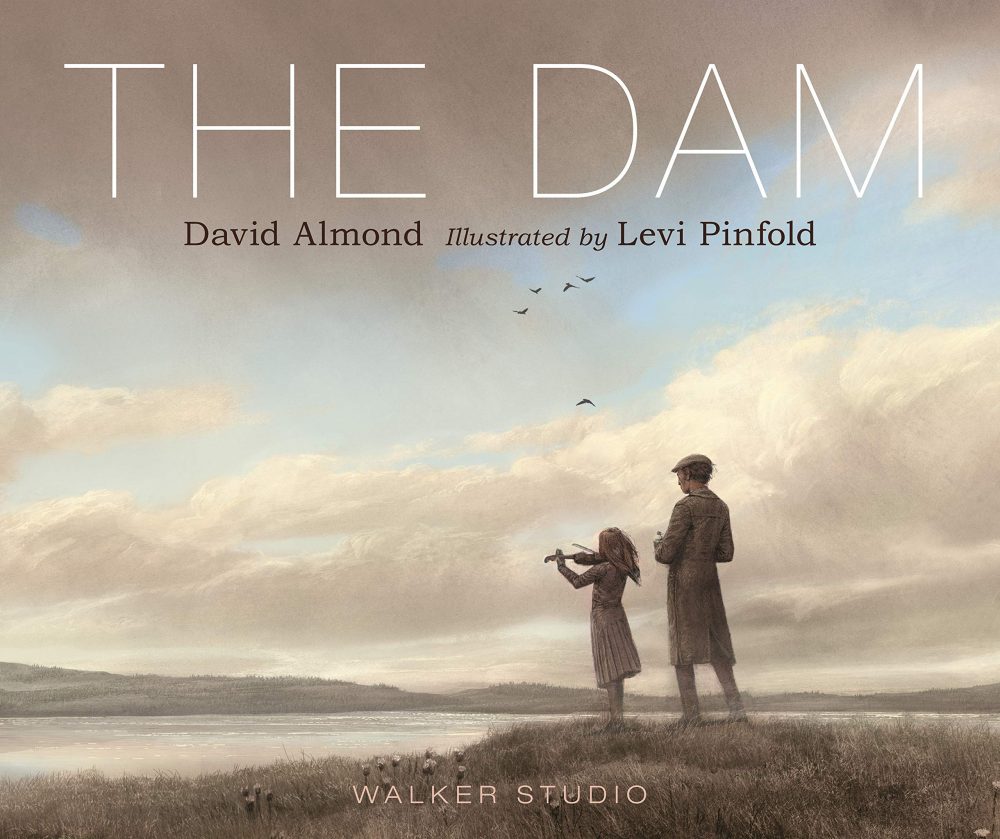

David Almond’s latest book is The Dam, illustrated by Levi Pinfold and published by Walker Studio. For more information about David Almond, visit his website here.

Lauren James’s latest books are The Starlight Watchmaker published by Barrington Stoke and The Quiet at the End of the World, published by Walker Books. Lauren James’s website is here

For more information about the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators Scotland Network click here.

Large image above : Elizabeth Frattaroli, David Almond, Lauren James and Justin Davies, (c) Edinburgh International Book Festival