Through Border Eyes: Sir Walter Scott and John Buchan

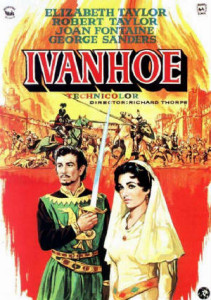

We all like to think we know about Sir Walter Scott; plenty of us have visited Abbotsford, his beloved Borders home – we may even have seen Ivanhoe (the film version, that is…), and most of us have been through Waverley station. But read his books? Aren’t they old-fashioned, difficult, rambling, melodramatic – and, worst of all, just plain boring? NO! says Donald Smith, director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre. The novels may be challenging, intriguing, sometimes downright odd – but dull they are not. And for those who had the privilege of hearing Donald read from some of them at the National Library of Scotland last week, the point was amply proved – at times the audience was left shrieking with laughter.

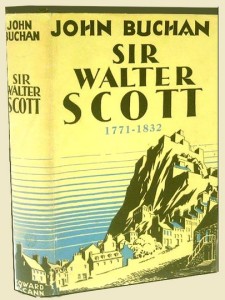

Donald took as his subject John Buchan’s Introduction to Sir Walter Scott, written in 1925 and soon republished as Sir Walter Scott; the Life and Work. Like Scott, Buchan was a Borders’ man, and shared Scott’s intimate feeling for the landscape and culture of ‘those debatable grounds’. Both men combined their writing with public careers (Scott in law, Buchan in diplomacy), and both matched a conservative political stance with wide human sympathy and understanding. Scott and Buchan also both wrote at times of war and unprecedented change; Scott perhaps saw his novels as providing people with an escape from the worries of the day, once saying that he had written them ‘to be read on stagecoaches’ – a bit like the airport blockbusters we buy today to take our mind off the serious stuff. Yet Scott’s writing, for all its high drama and colourful hyperbole, rarely fails to address the human condition; life, with all its many struggles and setbacks, is his inspiration.

Donald took as his subject John Buchan’s Introduction to Sir Walter Scott, written in 1925 and soon republished as Sir Walter Scott; the Life and Work. Like Scott, Buchan was a Borders’ man, and shared Scott’s intimate feeling for the landscape and culture of ‘those debatable grounds’. Both men combined their writing with public careers (Scott in law, Buchan in diplomacy), and both matched a conservative political stance with wide human sympathy and understanding. Scott and Buchan also both wrote at times of war and unprecedented change; Scott perhaps saw his novels as providing people with an escape from the worries of the day, once saying that he had written them ‘to be read on stagecoaches’ – a bit like the airport blockbusters we buy today to take our mind off the serious stuff. Yet Scott’s writing, for all its high drama and colourful hyperbole, rarely fails to address the human condition; life, with all its many struggles and setbacks, is his inspiration.

Walter Scott was born into Edinburgh’s middle classes in 1771. At the age of just two he contracted polio, which left him lame; he was sent to live with his grandparents and aunt in the Borders, where he soaked up the local legends and dialect. Returning to Edinburgh he became the playground storyteller, and later he was to use the Borders’ culture to create a new genre: historical fiction. Before Scott, poetry had been the literature of Edinburgh society; his novels, shaped by the tensions in Scottish life as much as by the inner conflicts of his characters, were a huge influence on Scottish and English culture, and still contribute to our self-understanding – Scott’s writing is, says Donald, ‘almost Shakespearean’.

Buchan and his publisher Thomas Nelson agreed that the Introduction should be a biography with literary illustrations. Buchan writes of Scott with sympathy, but not without a critical eye – Scott himself knew he could be superficial, ramble and lose the plot, but the extracts Buchan chooses are superb examples of Scott’s best traits. But are they entertaining? Donald began with a reading from Guy Mannering, a novel of almost contemporary life, full of gypsies, smuggling and Border adventures. Scott’s description of Meg Merrilies ‘her attitude was that of a sybil in full frenzy’ could equally well apply to Donald’s rendition of Meg’s farewell to Laird Ellangowan, as he threw himself into the role, arms akimbo, bringing out the melodrama of the writing as only a true storyteller could. The passion, the power, indeed the frenzy – all were there, matched only by the histrionic sensationalism of the moment. You could imagine how nineteenth century readers would have lapped it up; you didn’t need imagination to see twenty-first century listeners in the National Museum doing much the same.

Buchan and his publisher Thomas Nelson agreed that the Introduction should be a biography with literary illustrations. Buchan writes of Scott with sympathy, but not without a critical eye – Scott himself knew he could be superficial, ramble and lose the plot, but the extracts Buchan chooses are superb examples of Scott’s best traits. But are they entertaining? Donald began with a reading from Guy Mannering, a novel of almost contemporary life, full of gypsies, smuggling and Border adventures. Scott’s description of Meg Merrilies ‘her attitude was that of a sybil in full frenzy’ could equally well apply to Donald’s rendition of Meg’s farewell to Laird Ellangowan, as he threw himself into the role, arms akimbo, bringing out the melodrama of the writing as only a true storyteller could. The passion, the power, indeed the frenzy – all were there, matched only by the histrionic sensationalism of the moment. You could imagine how nineteenth century readers would have lapped it up; you didn’t need imagination to see twenty-first century listeners in the National Museum doing much the same.

Scott churned out the novels; within a year The Antiquary appeared, another contemporary novel featuring Elspeth’s Ballad,’a double agony of terror and suspense’ and one of the best, says Donald, that Scott ever wrote;

The cronach’s cried on Bennachie

And doun the Don and a’

And hieland and lawland may mournfu’ be

For the sair field of Harlaw.

In 1818 The Heart of Midlothian was on the shelves. Despite its serious story – it is based on the 1736 Porteous Riots in Edinburgh – it is, says Donald, full of humour, little ironies and digs at social pomposity. Scott was a great observer of character and many scenes are written in an affectionate tone, not least the heroine Jeanie Deans’ hilarious refusal of Dumbiedikes’ proposal of marriage. To hear Donald Smith read this passage was pure joy; Dumbiedikes cannot believe that Jeanie has refused his offer of riches and respectability, and is stunned by her admission that she is in love with the local minister Reuben Butler, exclaiming ‘Wilful woman will have her way!‘, a line just waiting for Donald’s animated and theatrical recital. As he observed ‘Some of Scott’s comments about marriage are not as romantic as you might have perhaps expected.’

And if you still think Scott looks like hard work….in 1820 he gave the waiting world Ivanhoe, a truly historical novel, and Scott’s attempt to breathe new life into the Middle Ages. Set in twelfth century England, it is a story of Saxons and Normans, crusades and conquerors, and of one heroic outlaw, Robin Locksley – otherwise known as Robin Hood. Scott travelled not only south of the border, but also to France and Switzerland to find material for this tale, the very one that forms the basis of all those films, TV series, and more merchandise than you can shoot an arrow at. Ivanhoe has, says Donald, a very visual structure and is unusual for the times in having a Jewish heroine, Rebecca; it introduces the idea of the stranger or outsider, of different cultures forced to meet.

And if you still think Scott looks like hard work….in 1820 he gave the waiting world Ivanhoe, a truly historical novel, and Scott’s attempt to breathe new life into the Middle Ages. Set in twelfth century England, it is a story of Saxons and Normans, crusades and conquerors, and of one heroic outlaw, Robin Locksley – otherwise known as Robin Hood. Scott travelled not only south of the border, but also to France and Switzerland to find material for this tale, the very one that forms the basis of all those films, TV series, and more merchandise than you can shoot an arrow at. Ivanhoe has, says Donald, a very visual structure and is unusual for the times in having a Jewish heroine, Rebecca; it introduces the idea of the stranger or outsider, of different cultures forced to meet.

After forays into Elizabethan history (Kenilworth, from which Donald gave us a stirring rendition of the Queen’s meeting with Amy in the garden), Scott returned to Scottish themes with Redgauntlet, set in 1765 Dumfries. A year later Scott was financially ruined, victim of a banking crisis and the collapse of the Ballantyne printing business. Donald’s reading of Scott’s writing about this time was particularly touching; Scott was determined to repay all of his debts and to avoid declaring himself bankrupt. Even at a time of great personal stress, he was more concerned about his tenants, his family and even his dogs and their rehoming, ‘I feel my dogs’ feet at my knee’ – how, he wonders, will the animals understand what has happened to them?

Scott decided to write his way out of disaster and he kept up his prodigious output right to his death at Abbotsford – the home he had worked so hard to keep – in 1832. His novella Castle Dangerous, published that year, shows, says Donald, a Scott drawn back to the Borders, the landscape that had been the great inspiration for all his works – just as Buchan’s last book Sick Heart River takes him back to the Canadian wilderness that he had come to love so much as Governor General.

Scott and Buchan, Donald concluded, always preferred accessible and entertaining storytelling; they wanted to give people something to sustain them through difficult times. Although some of Scott’s writing can resemble ‘the longest free-range shots in cinema’, he is ‘genial and relaxing company.’ If that is so, then Donald Smith is a worthy inheritor of Scott’s baton, a ‘champion of the interaction of art and life’, an animated and sympathetic storyteller breathing new life into one of Scotland’s most famous writers, helping to ensure that Scott will never become ‘The Great Unread.’

This event was part of the Scottish International Storytelling Festival 2014 and the Great Scott! Celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the publication of Waverley.