Talbot Rice Gallery : Christopher Orr

If every picture tells a story, each one of Christopher Orr’s paintings tells many. At first they may seem simple – if strange – depictions of people in natural scenes; rivers, mountain ranges, country roads. The figures are frequently in 1950’s clothes and we have no idea why they are where they are – but they’re still just people, right? Until we take a closer look and see not only that they are rather odd – a woman with a wide-brimmed sunhat on her head turns out to have no head at all…..another head floats in clouds – but that they are surrounded by other shapes and forms emerging from the landscape.

Until Only Mountain Remains, 2010. Christopher Orr. Burger Collection, Hong Kong.

In Until Only The Mountain Remains (2010) two girls in colourful pink and blue dresses stand on a white surface, backs to us, looking out across a sombre mountain scene – then in the shadows we begin to discern a huge white owl, head turned back, watching them. Other ethereal shapes appear…they could be peaks or clouds, or perhaps strange people, fantasy figures; half way down the ravine into which the girls peer, a bell seems to be suspended in air. Everything apart from the dresses is dark; browns, murky whites. Why are the women in this place, and how did they get here? The contrast is not only in the colours; the scenery is reminiscent of a Romantic nineteenth century vision of the sublime, but the women superimposed upon it are far more modern – perhaps the stock characters of a minor Hollywood film.

In The Beguiled Eye, a new exhibition at Talbot Rice Gallery (University of Edinburgh) and Christopher Orr’s first solo show in his native Scotland, our perceptions are constantly challenged and realigned. The title painting itself is a Dali-esque representation of an older man looking down into something hidden from us; he is surrounded by strange objects – a cameo of a younger man, a disembodied heart, a nail, a skull, a shoe, a wood stump. A tiny house in pale blue light provides a contrast to the darkness of everything else, until we notice that opposite the man a sapphire blue eye also shines out from a bird with a menacing hooked beak, and behind that bird there is another bird, with an eye that may be smaller but is just as blue. Returning to the left-hand side of the canvas we see that behind the man there is the shape of another man, also looking down. What are they looking at? And are all these objects the symbols they would be in a Renaissance painting, or something else? Caoimhin Mac Giolla Leith suggests (in the catalogue to Orr’s 2008 exhibition at Nyehaus, NY) that Orr’s work reflects ‘the Romantic disdain for reason’, but we can’t resist trying to find that reason, whether or not it ultimately exists.

Pat Fisher, Talbot Rice’s Principal Curator, describes Orr’s works as having ‘an illusionistic depth that moves beyond their physical scale and takes the viewer into a different world’. They are of course not the only paintings to do this, but in Orr’s case that world seems especially different and enigmatic.

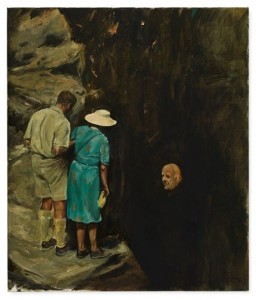

In Silent One (2010), a couple stare into a rocky crevice. They look as though they have just stepped out of an Agatha Christie novel – he in long khaki shorts and socks, she with sensible shoes and hat; they probably have a copy of Baedeker with them. As we follow their gaze, however, we see the floating head of an old man between the rocks. The sightseers are characteristically turned away from us, but although we cannot see their faces their stance suggests that they are neither shocked nor scared – they inspect this strange apparition in the same way that they would approach an archaelogical site or an unusual botanical specimen. Again we are provided with no answers, no apparent reason why these 1950’s people are walking about in such a bizarre landscape. In his wonderful and illuminating notebooks, exhibited here for the first time, Orr writes of ‘the possibility to be forced as the viewer to see (within) the painting various contradictions within the single viewpoint…..it is this quality that allows the painting to arise above discourse and the ‘sayable’ without having recourse to vagueness or mystification.’

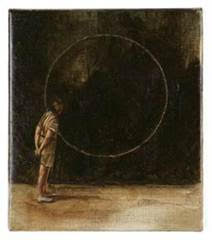

Geometric shapes feature in several of Orr’s works; All In A Moment Through The Gloom Were Seen (2014) shows a woman and two men sitting on rocks, their backs to us as usual, looking at unnaturally angular mountains…but in those mountains are the faceless shapes of people. What do these apparently impassive onlookers see? In Together We Sing (2013) a group of figures again sit looking out over a valley, a triangular shape rising above them and forming a frame to the vista, whilst Darkness Visible depicts a man looking into a circle drawn around part of a mottled dark brown surface. A similar framing device is seen in No Birds Do Sing (2014), when we seem to be looking through what could be a huge keyhole or a medieval window at a Turner-esque sky of wild, swirling clouds beneath which there is a tiny patch of red, possibly a boat.

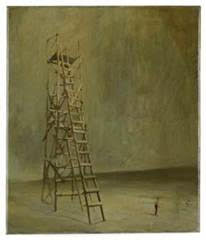

Orr frequently plays tricks with perspective too; Tower (2007) shows a moving scaffold of the kind used by artists to paint huge friezes or by circus performers climbing up to high wires – below is a tiny figure, a person who could not even reach the first step without difficulty. ‘Untitled’ (2007) reverses this; an enormous man in a carpenter’s apron seems to be attaching something (possibly a telegraph wire) to the top of a fir tree – a tree half his size. Is he huge or are the trees tiny? How are these terms defined?

Many of the paintings involve birds in one way or another – the white owl of Until Only The Mountain Remains, the strange hawk-like creatures of The Beguiled Eye – and in To Your Scattered Bodies Go garden birds seem suspended in space, some upside down, others perched on non-existent branches. A nest of eggs floats past. Orr’s notebooks reveal his fascination with cut-out figures; he appropriates images from sources as diverse as National Geographic magazines and old family photos, and these little birds recall Disney’s Song of the South (‘Mr Bluebird’s On My Shoulder’), whilst in one of the notebook pictures men stand among birds in a desert-like landscape or a beach. The men are holding the birds, picking them up, peering at them…..each man is identical, wearing the same baseball cap; they are possibly one and the same man. A collage in the notebooks is of bird pictures cut out and stuck on top of a woman in 18th century dress; the birds do not appear to be eagles, but they are somehow much bigger than the woman, swamping her.

Lying Muddy Humours (2014) is another whirlpool of dark browns, greens and murky yellows dotted with tiny points of pink….and once more closer inspection reveals heads – again perfect representations of 1950’s American men, the stuff that advertising was made from – drifting in space, whilst at the bottom of the canvas we can make out a railway shed or perhaps a gypsy caravan, recalling the tiny house in The Beguiled Eye. These are worlds, writes Fisher, ‘in which figures, often historicised and seen in Rembrandt-like chiaroscuro, appear trapped by natural phenomena…where the viewer cannot quite understand the narrative but is still drawn in.’

Orr’s work is full of dramatic possibilities, and Talbot Rice is inviting both academics and writers (or would-be writers) to draw on these to produce an imaginative response. On Monday 24th November four experts will give short public talks designed to inspire interest in the exhibition’s themes: Viccy Coltman looks at The Romance of Romanticism, whilst Kate McLean investigates Gothic Perspective: at the edge of the uncanny. Russell Jones considers Technophilia: dreamed technologies and technological dreams and Lena Wanggren concludes the evening with Gazing at the Technological Sublime. If you would like to attend this free event, book your ticket via eventbrite.

On 6th February next year creative writers Dilys Rose, Allyson Stack, Jane McKie and Russell Jones will lead a night of storytelling, reading new fictions inspired by The Beguiled Eye and a selection of public submissions, all celebrating the role of the imagination in interpreting art. To this end, the Gallery is inviting everyone to try their hands at providing an imaginative written response to the exhibition; flash fiction of no more than 1,000 words and/or poetry of up to 42 lines should be submitted electronically by 9th January 2015; for full details contact the Gallery or see its website.

This cryptic and atmospheric exhibition (generously supported by Hauser and Wirth, London, NY & Zurich) is on now at Talbot Rice Gallery, Old College, University of Edinburgh, South Bridge. The Gallery is open 10am-5pm Tuesday to Friday, 12 noon-5pm Saturdays, and The Beguiled Eye will close on 14th February 2015.

With thanks to Stuart Fallon at Talbot Rice.