The Scottish International Storytelling Festival 2014 – Mercat Tours

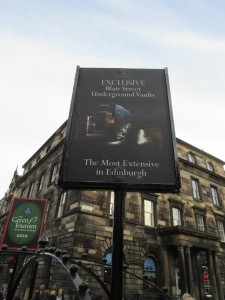

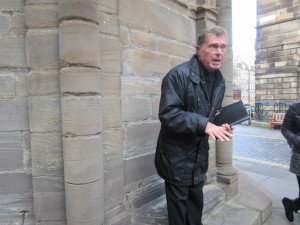

Think only modern architects make mistakes? Fondly imagine that if your house had been built in the 18th century you wouldn’t have that mouldy bathroom? Well think again! On Friday, as part of the Scottish International Storytelling Festival 2014, Mercat Tours guide William led a trip through the Old Town and down into the Blair Street (or South Bridge) Vaults; en route he shared some fascinating stories.

Think only modern architects make mistakes? Fondly imagine that if your house had been built in the 18th century you wouldn’t have that mouldy bathroom? Well think again! On Friday, as part of the Scottish International Storytelling Festival 2014, Mercat Tours guide William led a trip through the Old Town and down into the Blair Street (or South Bridge) Vaults; en route he shared some fascinating stories.

After explaining the grisly punishments meted out to ‘criminals’ at the Mercat Cross, and the stomach-churning sanitation arrangements in the old closes and wynds, William shepherded the group to the entrance to Blair Street and down a candlelit spiral staircase to the Vaults themselves, where he began by explaining how they first came into being.

After explaining the grisly punishments meted out to ‘criminals’ at the Mercat Cross, and the stomach-churning sanitation arrangements in the old closes and wynds, William shepherded the group to the entrance to Blair Street and down a candlelit spiral staircase to the Vaults themselves, where he began by explaining how they first came into being.

By the early 1800s, the Old Town had become unbearably overcrowded and insanitary, and plans were made to extend the city northwards. The Cowgate Gorge was in the way, so bridges were proposed, and in 1772 (after a false start, a partial collapse, and the loss of five lives) the first North Bridge opened. Financially, it had been a disaster – particularly when it was realised that most of the area was loose earth thrown down from the construction of older houses; much deeper foundations were needed, more debts were incurred – and another bridge was still needed to link the university and the Southside in general to the High Street and the New Town. No-one wanted to lose any more money (this was Edinburgh after all…), so plans were made to build shops and tenements on top of the new bridge, and vaults underneath it. The vaults would be used by small traders – cloth dyers, cobblers, taverners, milliners – thus providing income for the owners and more space for local businesses in a city where space was at even more of a premium than it is today.

The trouble started before the Bridge had even been opened; the rich old lady who had been chosen to perform the ceremony died a week before the appointed date, and – perhaps to save money, perhaps to avoid any rows about who should take her place – the city decided she would be as good dead as alive, and used her funeral procession to declare the Bridge open. Superstition being rife, local people were horrified; so far as they were concerned the Bridge was cursed, and many refused to cross it. Nevertheless, it was there, and plenty of tradesmen moved into the vaults.

Now vaults underneath houses, with rough earth floors, no windows, no fresh water, and certainly no lavatories, probably weren’t the best places to work – imagine being the boy whose job it was to take the pails up to the street for emptying….but pretty soon it became obvious that there were worse problems. In their haste to get the Bridge up and running, the builders had completely forgotten to put in any damp-proofing. Condensation started pouring down, floods were a regular occurrence; even now, as William pointed out as he led us through the chambers, stalactites can be seen growing from the top of the walls. After a time, even traders accustomed to life in the Old Town (which also had no lavatories, as it happens) had had enough. They moved out, and before long squatters moved in.

Now vaults underneath houses, with rough earth floors, no windows, no fresh water, and certainly no lavatories, probably weren’t the best places to work – imagine being the boy whose job it was to take the pails up to the street for emptying….but pretty soon it became obvious that there were worse problems. In their haste to get the Bridge up and running, the builders had completely forgotten to put in any damp-proofing. Condensation started pouring down, floods were a regular occurrence; even now, as William pointed out as he led us through the chambers, stalactites can be seen growing from the top of the walls. After a time, even traders accustomed to life in the Old Town (which also had no lavatories, as it happens) had had enough. They moved out, and before long squatters moved in.

The people who took over the Vaults ranged from local impoverished slum dwellers and families fleeing the Highland Clearances to criminals. In amongst them were ‘respectable’ members of Edinburgh society who wanted to meet in secret for their own reasons – cross-dressing, for example, was unacceptable to the strict Presbyterianism of the day – so where better place to do what you wanted to do amongst friendly faces? Illicit stills started up, providing the alehouses of the Cowgate with cheap liquour; the authorities turned a blind eye, especially as the ongoing war with France meant that little claret was entering the country – and with so many men away fighting it was hard enough to keep law and order above ground without worrying about what was going on below it.

The people who took over the Vaults ranged from local impoverished slum dwellers and families fleeing the Highland Clearances to criminals. In amongst them were ‘respectable’ members of Edinburgh society who wanted to meet in secret for their own reasons – cross-dressing, for example, was unacceptable to the strict Presbyterianism of the day – so where better place to do what you wanted to do amongst friendly faces? Illicit stills started up, providing the alehouses of the Cowgate with cheap liquour; the authorities turned a blind eye, especially as the ongoing war with France meant that little claret was entering the country – and with so many men away fighting it was hard enough to keep law and order above ground without worrying about what was going on below it.

This set of circumstances was, of course, perfect for a more sinister practice; bodysnatching. It was the time of Burke and Hare. A tunnel led from one of the vaults right to the centre of the old medical schools’ quad – there seems little doubt (although nothing has been proven) that it was used for transporting corpses. Snatched bodies – highly in demand at the time – could not be carried about in broad daylight (especially as they were taken naked, to avoid a sentence of transportation for theft of property), so they were probably stored in the Vaults until it was safe to take them into the university. It is also thought that bodysnatchers killed people living in the Vaults to add to their stockpile; it was unlikely that anyone would do much about the disappearance of the poor and the marginalised.

Eventually it was decided that all this nefarious activity had to be stopped. The Vaults were cleared – although this may have been as late as the 1870s – and filled up with tons of rubble and old stone from demolished tenements. What happened to the people who scraped a life under the Bridge? With no records surviving – or probably even kept in the first place – no-one knows. The Vaults were ignored and forgotten for many years, until in the 1980s they were rediscovered by property developer and former Scottish Rugby International Norman ‘Norrie’ Rowan; he and his son decided to excavate them, finding all sorts of artifacts along the way. Some of the chambers are now used as bars, clubs or storage areas, and Mercat Tours has the use of two, which you can see today. Mercat also has a new Discovery Room, where you can handle items found during the excavations, a sedan chair used by the wealthy to avoid the unsavoury middens beneath their feet, and lots of information about the Old Town.

Eventually it was decided that all this nefarious activity had to be stopped. The Vaults were cleared – although this may have been as late as the 1870s – and filled up with tons of rubble and old stone from demolished tenements. What happened to the people who scraped a life under the Bridge? With no records surviving – or probably even kept in the first place – no-one knows. The Vaults were ignored and forgotten for many years, until in the 1980s they were rediscovered by property developer and former Scottish Rugby International Norman ‘Norrie’ Rowan; he and his son decided to excavate them, finding all sorts of artifacts along the way. Some of the chambers are now used as bars, clubs or storage areas, and Mercat Tours has the use of two, which you can see today. Mercat also has a new Discovery Room, where you can handle items found during the excavations, a sedan chair used by the wealthy to avoid the unsavoury middens beneath their feet, and lots of information about the Old Town.

This was a fascinating and well-delivered tour; William clearly knows his stuff, and excelled at making history interesting for everyone, including the children in the group – one of whom he roped in to demonstrate the sorry lot of the 18th century sweep’s boy (whose average life expectancy was less than two years from his first ascent of a dusty chimney) – and though he certainly didn’t send little Aisling up the flue, she clearly enjoyed her moment in the limelight!

For more information about this and other daily tours run by Mercat, see their website or call into their office at 28 Blair Street.