The Physic Garden: an afternoon with Catherine Czerkawska

The Oxfam bookshop in Byres Road may seem an unlikely place to inspire a novel. For Catherine Czerkawska, however, the discovery of a book about the lost gardens of Glasgow University did just that. Living in a 200 year old cottage with a garden full of herbs, Catherine had long been interested in their medicinal properties; now she had come upon a strand of history in which they had played a key part. She was fascinated and immediately recognised a story that needed telling. On Saturday at the Central Library Catherine introduced her new novel, The Physic Garden.

The story is set in eighteenth century Glasgow; the city was industrialising, pollution was rife and people were fascinated by machines. Medicine, and more particularly surgery, was developing at a fast rate. It was the time of the resurrectionists, bodies were needed for experimental purposes. If machinery could be mended by engineers, why could bodies not be similarly repaired? Not with expensive drugs and rest cures but by a quick application of the knife – all the better now that so many people were being injured in factory accidents; how much cheaper to fix them fast and get them back to work.

The old college of Glasgow University (which was on High Street near the Cathedral) had several gardens. The Physic Garden was used to provide specimens for medical students to study, and Catherine’s reading showed that the Head Gardener in the late 1700s was one Robert Lang. Robert was struggling however; the university, in its increasing need for typeset for books, had allowed a foundry to be built next to the garden, with the result that the plants were dying from the effects of pollution from heavy metals.

Professor Jeffrey, a leading surgeon of the day, was also charged with delivering lectures in Botany to the medical students, but he found the study of plants boring; attendance (by which lecturers were in those days paid) became poor and chaotic, with the students at one point releasing a rat into the room just to liven things up. Delegation of academic duties was perfectly acceptable, so Jeffrey passed his duties to Dr Thomas Brown, an enthusiastic physician and botanist. Thomas needed plants; the garden could no longer provide them, so he enlisted the help of Robert Lang’s son William, then an under-gardener, to go out into the countryside to collect specimens for his classes.

When Robert died suddenly the university made William its head gardener at the age of only 19. The gardens were dying; the university blamed William, who was also now faced with supporting his mother and seven younger siblings. He tried to set up a pharmacy – a business that was traditionally handed down from mother to daughter – but the lack of good plants from the garden and his mother’s lack of pharmaceutical knowledge meant that the project failed. In the end, and despite many supporting letters written by Thomas, William was sacked. This much Catherine learned from her research; her imagination was sparked, and she started to wonder about William’s life, his friendship with Thomas, and what might have happened to them both. She found some information about a printer and publisher working in Glasgow at the relevant time: his name was William Lang. Could they have been the same person? Living beside the college, William would have had more access to books than most young men of his class, and would probably have borrowed them from Thomas. What irony if William, whose gardening career had been killed off by the type foundry, had ended up making his career in books: Catherine had her story.

In the novel, narrated by William as an old man, he meets a young girl, Jenny, on one of his plant-hunting trips. Despite their growing relationship Jenny remains a shadowy figure; at one point Catherine’s then agent suggested writing the book in the third person, which would have enabled her to see inside Jenny’s head, but after a couple of chapters Catherine found that this just did not work; William’s voice was so strong that he had to tell his own story. Catherine also points out that in those days women’s voices counted for less; the friendship between William and Thomas, though it was always platonic, may well have been more important to William than any relationship with a woman. Catherine’s research showed that Thomas was only a few years older than William and although there were vast differences between them in background and wealth they had so much else in common that they formed a friendship rare at that time. For Catherine there are similarities between this and the intimacy between Robert Burns and Gavin Hamilton; a closeness that comes from shared interests and enthusiasms, an understanding of what makes each other tick.

William and Thomas have unfulfilled dreams of leaving Glasgow to look for plants in China or the Americas; many people did make such journeys at the time – our modern gardens reflect this – but they were generally far wealthier than William or even Thomas, and many died in their efforts. William and Thomas do make it to Arran – Catherine discovered that there was at the time a hunt for specimens of the Arran Service tree, which grew only on the island. Research, she says, can sometimes lead a writer off at a tangent that turns out to be perfect for a plot; in this case it allowed her to get William and Thomas out of Glasgow, showing us further aspects of their friendship.

We are aware from the opening pages of the book that something cataclysmic has happened between Thomas and William. Now in his 70s, William is trying to come to terms with the past, something he has avoided thinking about for many years. The story considers how we can look back with the wisdom and perspective that come with age; do they help us to resolve the events of our youth, or do they simply bring us more pain?

William, says Catherine, must be seen as a slightly unreliable narrator in that he has no time for Professor Jeffrey (who in turn has no time for plants) despite Thomas’s defence of him. He is, she says, a very interesting and clever man who deserves a book to himself. Although he was involved in the rather gory reanimation scene in the book, she is sure that he knew it would never work – he just wanted to see how a dead body would react, and also to gain as much publicity as possible to help fund his own work in pioneering surgical procedures (the experiment was carried out in public on the corpse of a murderer, and was a very popular event – it is said to have inspired Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein.) Jeffrey invented the chainsaw (‘to relieve patients’ pain’) and wanted to help people.

Catherine is an award-winning author who has written seven other novels, many plays and short stories and has worked in Finland, for the British Council in Poland and for Fife Community Arts. She has a University of Edinburgh degree in English with Medieval Studies and a Masters Degree in Folk Life Studies from Leeds University. The amount of research she undertakes varies from book to book – in this instance she already had knowledge of the medieval period but needed to investigate the medical world of the time. She has a facsimile copy of one of the books mentioned in the story but had to go to Glasgow University to see the facsimile of another, a tome full of alarming and distressing pictures. She also read the stories of some of the great plantsmen of the day, but says that there comes a point when research has to stop and the writing begin, even when that means going back to do more later on. William’s voice was so strong to Catherine that she originally thought of writing a stage production – she had recently been working for The Oran Mor theatre – but it soon became obvious that there was far too much material for a short play. She sat down to write the novel and once she had started she hardly stopped. Although the book has been to an editor very little of the original structure has been altered, ‘It was as though William was telling me the story himself.’ Catherine had her ups and downs with agents (one telling her ‘this is just an old man telling his story, no-one will want to read that’), but once the book was accepted by Sara Hunt of Saraband Books she acquired an excellent editor who helped her and Sara to see what the story needed to make it work, ‘A good editor is a pearl of great price.’

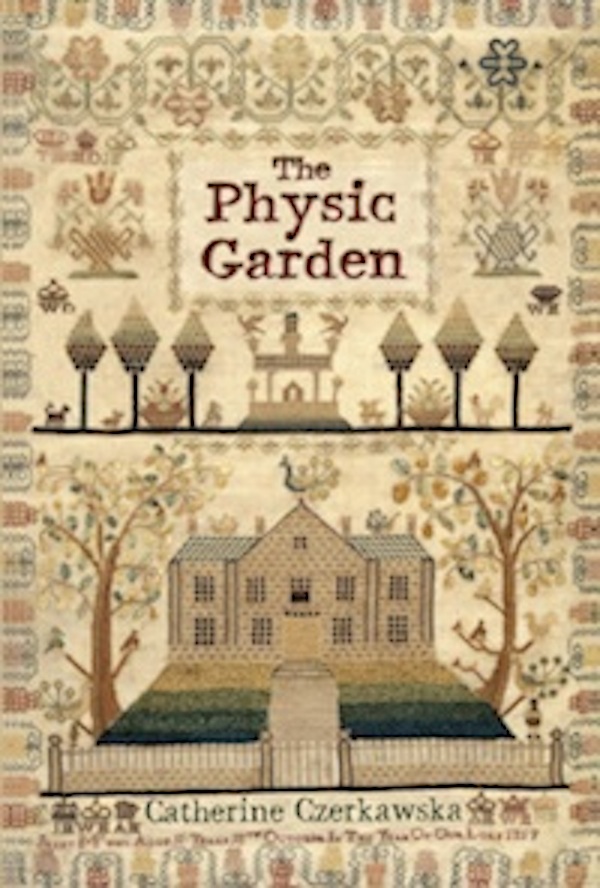

Sara’s was also the inspiration for the book’s cover, an eighteenth century sampler. Catherine was delighted with the idea and Rebecca Quinlan of the Burrell Collection came up with Janet McNiel’s beautiful work, dating from 1819.

The Physic Garden is a story of contrasts: old age and youth, friendship and enmity, growth and decay. It opens our eyes to a pivotal period in Glasgow’s history, but it is also a timeless story of life and death, choices and consequences.

Once again Annie Bell (Reader Development) is to be congratulated on bringing another excellent event to the library.

The Physic Garden by Catherine Czerkawska is published by Saraband Books and is available from The Edinburgh Bookshop, 219 Bruntsfield Place.