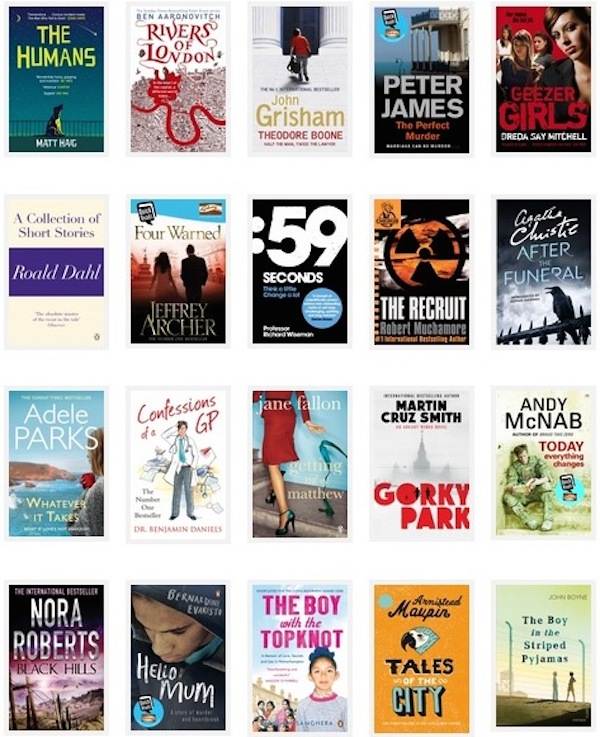

World Book Night 2014 at Blackwell’s

Anthony Horowitz has said of Roald Dahl, ‘He finds the adult in the child and the child in the adult, and sticks the knife into both.’ On Wednesday night at Blackwell’s, Jenni Fagan introduced Expect the Unexpected, Dahl’s second volume of short stories, as her choice from the World Book Night 2014 selection.

Fagan, herself a prize-nominated poet and celebrated author of The Panoptican, joined Jim Crumley and Angela Jackson, each of whom had been asked to talk about one WBN book and one of their own personal favourites.

Fagan explained that she has loved Dahl’s work since reading him as a child, seeing his anarchic, funny books as a bridge between children’s and adults’ fiction. There is, she says, a certain justice in his stories; they are moral but never preaching. In this collection she especially likes ‘Peg’, the tale of a man hurrying through a foreboding city in a vain attempt to outrun his fate. Inspired to find out more, Fagan discovered that Dahl had seen a man with a white face running through New York, where he was then living with his family; from this small event had grown a story.

Fagan’s own recommendation was Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Celine, a novel with such a dense and bizarre plot that ‘no modern publisher would consider it.’ Celine, who fought on the front in World War I, and whose sometimes antisemitic views caused much controversy, was, says Fagan, a stylist who changed the way people wrote, his novel ‘a big adventure story that was the start of nihilism.’

Fagan’s own recommendation was Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Celine, a novel with such a dense and bizarre plot that ‘no modern publisher would consider it.’ Celine, who fought on the front in World War I, and whose sometimes antisemitic views caused much controversy, was, says Fagan, a stylist who changed the way people wrote, his novel ‘a big adventure story that was the start of nihilism.’

Jim Crumley has been described by the LA Times as ‘the best nature writer working in Britain today.’ A former journalist, he is the author of 26 books: his latest, The Eagle’s Way, has just been published by Saraband; he also writes poetry and contributes to radio programmes., but is not a fan of much ‘wildlife TV’, which he feels crams years of observation into thirty minutes of distorting screen time. Crumley introduced his WBN choice, John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, with a disclaimer: he doesn’t like war, and sees the constant revisiting of it, and particularly the current year-long commemoration of World War I, as a peculiarly British thing. He would never write about war, nor buy most books about it, but for him The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas brings the focus down to a few human beings and ‘cuts through the chaos of war.’

When Crumley opened the novel, its language sounded strangely familiar. He read out the first paragraph of Winnie the Pooh to the audience to show how Boyne seems to replicate AA Milne’s rhythms and devices: capital letters are used in Significant Phrases, and both Pooh and Bruno’s childish misuse of words gives their thoughts greater resonance, as when Bruno refers to the Fuhrer as ‘the Fury.’ Both stories, says Crumley, are written from a child’s level; Bruno and Pooh are both small, and share a childlike sensibility to their worlds. Bruno walks around the Auschwitz perimeter fence, sees the boy in his striped pyjamas, realises that everyone inside the enclosure is similarly dressed, but does not know why. He sees the smoking chimney but does not know what it is. Boyne somehow takes a terrible story and makes it into one that grips children; Crumley says that he is still unsure whether he sees Boyne as brave or stupid, but he nevertheless highly recommends this novel.

When Crumley opened the novel, its language sounded strangely familiar. He read out the first paragraph of Winnie the Pooh to the audience to show how Boyne seems to replicate AA Milne’s rhythms and devices: capital letters are used in Significant Phrases, and both Pooh and Bruno’s childish misuse of words gives their thoughts greater resonance, as when Bruno refers to the Fuhrer as ‘the Fury.’ Both stories, says Crumley, are written from a child’s level; Bruno and Pooh are both small, and share a childlike sensibility to their worlds. Bruno walks around the Auschwitz perimeter fence, sees the boy in his striped pyjamas, realises that everyone inside the enclosure is similarly dressed, but does not know why. He sees the smoking chimney but does not know what it is. Boyne somehow takes a terrible story and makes it into one that grips children; Crumley says that he is still unsure whether he sees Boyne as brave or stupid, but he nevertheless highly recommends this novel.

Ring of Bright Water was made into a blockbusting film when I was a child; I never went to see it after my friend told me the otter died. (I had the same trouble with Black Beauty and Bambi.) Crumley is made of sterner stuff; he first read Gavin Maxwell’s book at the age of 18; ‘by the time I was half way down the first page I was helpless.’ As soon as he got to the end he read it again, and he has loved and admired it ever since, seeing it as an object lesson on how we treat the world and nature. He describes Maxwell’s writing as ‘astounding but dense, and as challenging as an Islay malt’ and describes it as having a painterly style (Maxwell was also an artist); for Crumley there is no better landscape writer. Before Ring of Bright Water was published, otters were seen as vermin; the book single-handedly changed that attitude and the otter is now one of the best-loved and best-protected animals in the UK. The book is, says Crumley, the work of a troubled but unarguable genius.

59 Seconds by Richard Wiseman is a book about happiness, and how we can have more of it. Angela Jackson, (whose first novel The Emergence of Judy Taylor won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award), is a psychology lecturer who teaches a course at Edinburgh University on this very subject. Jackson believes that we all have the ability to live more happily, but she also thinks most self-help books are a waste of shelf space. Wiseman’s book is, she says, different; he does not pretend to have all the answers, but he does look at scientific research and sort out the good stuff from the twaddle.

According to Wiseman, 50% of our happiness is genetically determined, 10% is circumstantial, but the rest depends on how we live our daily lives. He asks everyone to keep a daily journal with three components: (i) gratitude (ii) future projections and (iii) ‘affectionate writing.’ Wiseman claims that listening to Vivaldi can lower stress levels, spending 30 minutes a day in the sun can improve your memory and having a pot plant on your desk can increase creativity. He is particularly keen on the value of altruism and says that small acts of kindness to others can increase your own happiness levels by 40%. Jackson likes this book because it suggests lots of small things that we can all do to increase our happiness and our resilience. Here in Edinburgh, we may not have too much control over the sunshine, but we can still practise loving kindness.

Jessie Kesson was born to a prostitute in the Inverness workhouse in 1916. By the time she died in 1994 she had become a BBC producer and worked on Woman’s Hour. In between was a life of great hardship, but also one of great love. Kesson’s semi-autobiographical novel The White Bird Passes was Jackson’s second book choice, one she discovered when taking a module on Scottish Women’s Fiction. As a young child Kesson lived in a poor but close-knit community; she was extremely close to her mother – ‘I would myself be blind now if she had not lent me her eyes’, from whom she gained a rich informal education. When her mother developed syphilis, Kesson was sent to an orphanage in Aberdeenshire, and despite being encouraged by her teacher to apply to university, was refused permission by the institution’s trustees, who made her go into domestic service at a young age. She lived in Aberdeenshire for many years before moving to London. Jackson sees Kesson as a hugely under-rated author, and particularly admires her writing style, quoting her description of ‘wildflowers smelling like heartbreak if heartbreak could smell.’

All three authors stressed how important reading is to them as writers. Both Jackson and Fagan advised aspiring novelists to write whenever they could – Jackson wrote her book from midnight to 3am whilst still holding down a full-time job, Fagan had just had a baby when she wrote hers; she even read the less pleasant bits out to him ‘in a nice voice.’ Both stressed the need to be ‘mercenary’ with time, and to ignore the inner voice telling you that you’re not a valid person unless you’re earning money. Crumley has not ever had to fit writing round another job, but he too emphasised that a writer needs to want to write more than anything else, saying that having no other means of financial support certainly concentrates the mind. After 26 years, writing still has the capacity to surprise him.

Three authors, six very different books; an interesting and stimulating evening. I’ve been thinking about which books I would have chosen; for me it would have to be Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City and Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women. Which books would you give away on World Book Night? Share your thoughts with us; as The Reading Agency says, ‘Everything changes when we read.’