Edinburgh International Book Festival – John Sutherland and John Crace

(Karen Howlett writes the lovely Cornflower Books which is all about ‘books and other good things’.)

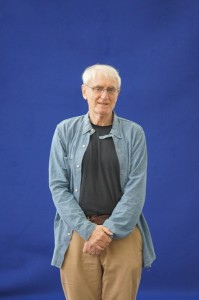

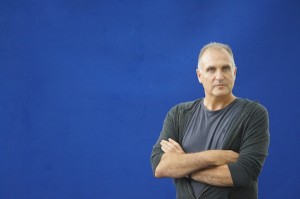

Back to the Book Festival today to hear Professor John Sutherland talking about fiction with reference to the personalities and predilections of those who create it, all brought together in his massive new book Lives of the Novelists: A History of Fiction in 294 Lives, and John Crace, the writer behind The Guardian Digested Read column and author of Brideshead Abbreviated: The Digested Read of the Twentieth Century.

This was such an entertaining hour, and John Sutherland alone would enthuse even a reluctant reader, I feel, but he, along with “the young John” delighted what must have been a very well-read audience. He began by telling us that although he taught literature for forty years, he really only read books at two periods of his life – when he was very young, and once retired. Growing up in Edinburgh in the 1940s and ’50s, he described the books he discovered in those dark post-war days as a passport to another world, and now much later in life he calls fiction “a fantasy factory”, food for the imagination, and it is from that passion that his Lives has sprung.

Leaving behind the academic world which requires the reader to “keep their eyes on the page”, he is now free to indulge his interest in literary curiosities, puzzles, irrelevancies and details, and he is recapturing some of the magic which fiction has always had for him, responding to a book as an agent, not a passive receiver, and following the trails laid by books themselves or by events great and small in their writers’ lives.

Being in Edinburgh on this very rainy day, he was reminded of the circumstances which led Robert Louis Stevenson (a local) to writeTreasure Island. In 1880, the Edinburgh summer was marked by weather which was bad by even Scottish standards, and RLS, whose health was poor, was advised to move up to Deeside for better air. There was no respite from the rain there either, and Louis’s young stepson Sam was forced to occupy himself indoors. He had a set of watercolours and a room he called his ‘studio’, and based on the tales of derring-do and boys’ own adventures that he’d been reading, he set about painting a treasure map, his artwork the prompt for Louis to start telling him stories based around it, the opening of Treasure Island thus being drafted one evening at the fireside. Had the sun shone that summer, says Prof. Sutherland, we would not have that book!

Being in Edinburgh on this very rainy day, he was reminded of the circumstances which led Robert Louis Stevenson (a local) to writeTreasure Island. In 1880, the Edinburgh summer was marked by weather which was bad by even Scottish standards, and RLS, whose health was poor, was advised to move up to Deeside for better air. There was no respite from the rain there either, and Louis’s young stepson Sam was forced to occupy himself indoors. He had a set of watercolours and a room he called his ‘studio’, and based on the tales of derring-do and boys’ own adventures that he’d been reading, he set about painting a treasure map, his artwork the prompt for Louis to start telling him stories based around it, the opening of Treasure Island thus being drafted one evening at the fireside. Had the sun shone that summer, says Prof. Sutherland, we would not have that book!

John Sutherland then introduced John Crace, describing his digested reads as the equivalent of “turning a cow into an Oxo cube”, and paying tribute to how carefully he reads the texts he parodies, coming up with an end product which is “both itself and something else … not so much a hatchet job, more dissection with a surgeon’s scalpel”, and providing an example of deflation in a world of literary hype. We were treated to a reading of two of his columns, his deconstruction of David Copperfield, marking Dickens’ bicentenary, and Antonia Fraser’s Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter

John Sutherland then introduced John Crace, describing his digested reads as the equivalent of “turning a cow into an Oxo cube”, and paying tribute to how carefully he reads the texts he parodies, coming up with an end product which is “both itself and something else … not so much a hatchet job, more dissection with a surgeon’s scalpel”, and providing an example of deflation in a world of literary hype. We were treated to a reading of two of his columns, his deconstruction of David Copperfield, marking Dickens’ bicentenary, and Antonia Fraser’s Must You Go?: My Life with Harold Pinter which he read in a suitably high-pitched voice; both had the audience in stitches.

John Sutherland then took up the Dickens theme with a discussion of the debate over the events of Dickens’ death: did he die at Gads Hill Place, as the first authorised biography says, or was it at Ellen Ternan’s house with his body later returned to the family home? Did he lead a double life, was he a cruel husband, or was he a decent man who helped a woman in difficulty? Versions of his life abound, and successive biographical works – most recently The Great Charles Dickens Scandalby Michael Slater – present evidence for both theories.

In answer to a question from a member of the audience, the two Johns talked briefly about defining ‘the classics’. John Sutherland quoted the late Frank Kermode: “Old books which people still read; books which cross boundaries,” and felt the term ‘modern classic’ was a contradiction in terms. John Crace noted that the later one goes in time, the more arbitrary the benchmark seems. He cited Salman Rushdie’s 1981 Booker Prize winner Midnight’s Children and said he had done a straw poll on the book canvassing 40 members of staff at his newspaper. 30 had not read it, four had tried and given up, four had finished and hated it, and only two loved it – perhaps not a scientific study, but an interesting result nonetheless for a novel which has apparently achieved ‘modern classic’ status.

An hour was too short a time to fully savour all that “The Two Johnnies” – as they are sometimes called – had to say about books and writers. I could have listened to them all afternoon.

This article was published first on Cornflower Books.